We are legion

by Bill Landers

[email protected]

In the January 2009 issue, I described how differences in the bacteria in our intestines make some people fat and others lean. These bacteria provide up to 30% of our daily energy needs by fermenting simple and complex sugars, carbohydrates, plant cellulose, and fruit pectin.

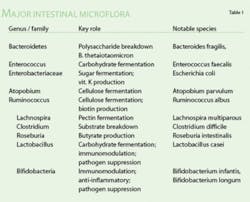

Here are some more little known facts about the legions of bacteria that call our guts home [Data from Stud BMJ, 2008;8(12)]. Our intestines are home to 100 trillion individual microbes belonging to 36,000 different species. Think of it; 90% of the cells inside our bodies aren't even human, but by providing them a home, we benefit from a bacterial gene pool 100 times larger than our own. Most of them live in the anaerobic large intestine (colon) where they earn a living by fermenting foods that we can't, producing vitamins, regulating the immune system, and even producing antibiotics to fight off harmful bacteria. Roseburia, for instance, produces butyrate, which has anti–colon cancer properties (see Table 1).

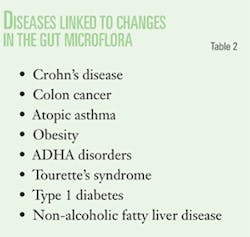

The bacteria also produce bacteriocins (antibiotic peptides) and ferment harmful acids and help prevent pathogenic bacteria from colonizing the gastrointestinal tract. Given their importance, it's hardly surprising that any disruption (antibiotics, for example) allows opportunistic pathogens to cause a wide range of health problems (see Table 2).

We're not born with our symbiotes. Babies have to acquire them from maternal milk and the gut microflora isn't stable until after weaning. Bottle–fed children typically have higher proportions of pathogenic bacteria than breast–fed children. Early antibiotics can disrupt a healthy gut microflora for years afterward.

Colonic bacteria provide us with essential nutrients like biotin, folate, and vitamin K, promote growth, and fight infections. Sometimes, because of human genetic mutations, our immune systems mistake good intestinal bacteria for bad, resulting in the intestinal inflammation characteristic of Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. It's also suspected that an atypical gut microflora can liberate toxins from foods and cause diseases such as Tourette's syndrome, Type 1 diabetes, and ADD.

So, with 100 trillion gut bacteria, how does our immune system know which bacteria are good and which are bad? Most bacteria wind up in the colon because the stomach and small intestine are coated with a thick mucus and waves of peristalsis move them quickly along. The colon is the main interface between the immune system and our stomach's bacteria. It contains 75% of the body's lymph glands and 80% of the B cells that produce antibodies and immunoglobulin A that selectively neutralize pathogenic proteins and toxins.

The inner wall of the colon is lined with a single layer of epithelial cells. They not only absorb nutrients but form an essential part of our immune system. Breaks in the epithelial lining exposes bacterial and viral receptors that produce cytokines to mobilize the rest of the immune system.

So, the bacteria in our colon don't just provide extra calories. They extract and produce essential nutrients and, even though they are alien cells, they are an integral part of our immune system. We are all individuals, but each of us is legion.