Decoding the language of clinical attachment: Clarifying the fundamentals of staging, grading, and CAL

What you'll learn in this article

- The fundamentals of staging and grading periodontitis under the 2017 AAP/EFP classification system

- Why clinical attachment level (CAL) is the most reliable measure—and how common misconceptions lead to diagnostic errors

- How probing depth reliance, training variability, and software defaults contribute to misclassification in periodontal diagnosis

- The implications of documentation gaps for treatment planning, student education, and patient outcomes

Editor's note: This is part two of a three-part series. Read part one.

Accurately staging and grading periodontitis is critical for diagnosis, treatment planning, and communication, yet confusion remains—most often surrounding the correct calculation and application of clinical attachment level (CAL). As outlined in part one of this series, these challenges are compounded by inconsistent clinician calibration and software platforms that default to misleading values when gingival margin levels are not recorded. The result is diagnostic variability that affects both clinical outcomes and student learning in educational settings.

Part two of this series focuses on clarifying the fundamentals of staging, grading, and CAL, while addressing common misconceptions that persist in practice. By understanding where errors originate—whether through probing depth reliance, software limitations, or training variability, we can identify what must change to achieve greater accuracy and consistency. This discussion paves the way for part three, which will turn to emerging solutions such as radiographic interpretation, artificial intelligence (AI), and advanced digital tools designed to transform periodontal diagnosis and standardize clinical practice.

Understanding staging, grading, and common misconceptions

In 2017, the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) in collaboration with the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) undertook a comprehensive revision of the 1999 periodontal disease classification system, culminating in a modernized framework published in June 2018.1 This new system categorizes periodontitis based on both staging and grading, providing clinicians with a structured approach to assess the presence of disease as well as the display of severity, complexity, and risk of progression.

The key reasons for the update included:

Clinical ambiguity and overlapping categories: Previous classification systems differentiated chronic from aggressive periodontitis, relying heavily on age and disease rate—a distinction that proved unclear and inconsistent, especially in the absence of prior patient histories. These categories often overlapped, and clinicians found them difficult to apply reliably.

Advances in scientific evidence: Since 1999, large epidemiological studies and basic science research—including insights from the Human Microbiome Project and inflammation biology—highlighted the need for a classification scheme grounded in current understanding of etiology, progression, and host risk factors.

Need for standardization: A globally consistent framework was necessary to improve research uniformity, help compare epidemiological data, guide treatment planning, and support population-level health monitoring. The staging and grading model parallels other medical disciplines—such as oncology—helping clinicians personalize care and manage disease complexity effectively.

Inclusion of peri-implant disease: Implant dentistry has become widespread, yet the 1999 system lacked any classification for peri-implant health or disease. The 2017

update incorporated definitions for peri-implant mucositis, peri-implantitis, and tissue deficiencies around implants.

Multidimensional staging and grading: The new system replaces previously rigid, one-dimensional, age-based labels with a two-axis approach—staging, based on severity and complexity, and grading, which integrates risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, and rate of progression. Grading individualizes treatment plans and improves prognostic accuracy.

Staging of periodontal disease

Staging reflects the severity and extent of tissue destruction caused by periodontitis. The staging system is divided into four levels (table 1).

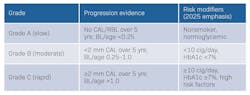

Grading of periodontal disease

Grading provides insight into the rate of disease progression and identifies factors that influence prognosis and responsiveness to therapy. Additionally, grading indicates the concern with which periodontal conditions may create a greater systemic impact. Grades are categorized as seen in Table 2.

Manual inputs and misclassification: Where confusion arises

Although the 2017 AAP/EFP classification was updated to bring greater diagnostic clarity, adaptability, and clinical relevance, as mentioned earlier, it is evident there is much confusion around the definition and application of clinical attachment level/loss.

Accurate documentation of interdental CAL helps prevent misclassification of early periodontitis as gingivitis. Understanding how to correctly measure and apply CAL is essential for consistency and clarity in periodontal diagnosis. Many clinicians default to probing depth alone when assessing periodontal destruction, overlooking the critical role of gingival margin position in accurately determining CAL. This diagnostic gap becomes even more pronounced in dental management software systems that fail to account for gingival margin variations unless the clinician inputs them manually, leading to potentially significant misclassification of disease.

Clinical attachment level requires two measurements

CAL is calculated by combining:

- Probing depth (PD)

- Gingival margin (GM) position relative to the CEJ (positive when recession, negative when gingival overgrowth, zero when gingival attachment remains at the CEJ with a corresponding healthy sulcus). Example illustrated in Figure 1.

If the GM is not recorded (positive or negative), the software (or the clinician) defaults to calculating CAL as the probe depth reading. This overlooks the true clinical findings:

- CAL in health on an intact periodontium: should be zero; junctional epithelium is at the CEJ

- CAL in gingival inflammation or pseudo pocketing: recorded as a negative to indicate the amount of tissue overgrowth in mm

- CAL in periodontal destruction/attachment loss: recorded as a positive to indicate the amount of apical migration of the junctional epithelium from the CEJ

Why hygienists skip gingival margin entry

Time pressure in clinic: Entering PDs for every site is already time-consuming, so clinicians may skip GM entries unless obvious recession is present.

Misconception: Many hygienists believe CAL = PD unless recession is obvious, prompting them to insert GM values when the gingiva has receded. This misses negative margins (pseudo pocketing noted as tissue coronal to CEJ).

Training variability: Dental insurance policies and dental hygiene programs often emphasize probing depth more than CAL, so students carry this habit into practice.

Calibration issues: Faculty and clinicians may not be calibrated consistently on identifying the CEJ or recording GM values.

Software default to CAL = pocket depth

Most dental charting software systems default CAL to the recorded probing depth when GM is not entered. This creates several issues:

Diagnostic errors: Inaccurate CAL affects staging and grading of periodontitis. For example, a patient with 5 mm PD and 2 mm recession (true CAL = 7 mm) may be staged lower if the position of the GM is ignored. Conversely, if a patient with a 5 mm PD has the gingival margin located 3 mm coronal to the CEJ, -3 mm should be entered under GM, giving the patient an actual 2 mm of CAL; if the -3 is not recorded, CAL calculates to 5 mm, which is incorrect and overstages the patient.

Accreditation/legal concerns: Inaccurate documentation can lead to under- or overdiagnosis, improper treatment planning, and liability concerns if records are reviewed.

As a result, clinicians are often left to navigate around the limitations—either skipping steps or manually entering detailed information, which is inefficient and increases the risk of documentation errors. When the workflow isn’t streamlined, dental hygienists may be less inclined to apply the classification consistently.

Moreover, the absence of built-in guidance or decision-support features reduces opportunities for ongoing learning and practical reinforcement. In some cases, platforms still use outdated diagnostic terms, further contributing to inconsistency and miscommunication among team members. When the digital infrastructure does not align with current clinical guidelines, it creates a disconnect between evidence-based practice and day-to-day operations.2

Until software companies update their periodontal assessment platforms to better accommodate the 2017 classification—and provide adequate training on how to use these updates—hygienists may continue to face barriers in applying the system effectively. Addressing this technological gap is crucial for improving diagnostic accuracy, communication among providers, and overall periodontal care outcomes.3

Conclusion

Despite the clarity intended by the 2017 AAP/EFP classification system, the accurate use of clinical attachment level remains a stumbling block. Missteps in documenting gingival margin position, coupled with variability in training and the limitations of charting software, continue to cause inconsistencies in staging and grading. These gaps impact not only treatment planning and patient outcomes but also the calibration of faculty and the confidence of students learning to apply the system.

Addressing these challenges requires more than refining manual techniques—it calls for innovation. As we move into part three, the focus shifts toward emerging solutions such as radiographic interpretation, artificial intelligence (AI), and advanced digital platforms. These tools have the potential to standardize diagnosis, improve accuracy, and better equip both clinicians and students for the future of periodontal care.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the November/December 2025 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions – introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S1-S8. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12935

- Zheng K, Ratwani RM, Adler-Milstein J. Studying workflow and workarounds in electronic health record-supported work to improve health system performance. Ann Intern. 2020;172(11 Suppl):S116-S122. doi:10.7326/M19-0871

- Mahesh Batra A, Reche A. A new era of dental care: harnessing artificial intelligence for better diagnosis and treatment. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49319. doi:10.7759/cureus.49319

About the Author

Marianne Dryer, MEd, RDH

Marianne Dryer, MEd, RDH, is a dynamic speaker, educator, and consultant in curriculum development. She has lectured nationally and internationally on periodontal instrumentation with a focus on ultrasonic technique, risk assessment, infection prevention, and radiology technique. Her experience in dentistry spans more than 30 years. She is currently the Director of Dental Sciences at Cape Cod Community College. She is a graduate of Forsyth School for Dental Hygienists, Old Dominion University, and received her master’s in education from St.Joseph’s College of Maine. Contact her at [email protected] or through her website at mariannedryer.com.

Katrina M. Sanders-Stewart, MEd, BSDH, RDH, RF

A clinical dental hygienist, author and international speaker, Katrina is passionate about elevating the dental profession by creating an undeniable movement that educates, encourages, and empowers the profession to rise in its power. Known as the “Dental WINEgenist™,” she pairs her desire for excellence in the dental industry with her knowledge and passion for wine. She is the Clinical Liaison for Hygiene Excellence at AZPerio, founder of Sanders Board Preparatory and has been published in various publications including RDH Magazine and Dental Academy of Continuing Dental Education. Recently, Katrina proudly received the University of Minnesota Distinguished Alumni Award and the 2024 Sunstar Award of Distinction. @TheDentalWINEgenist [email protected].