Oropharyngeal cancer and the human papillomavirus: The importance of the HPV vaccine

Life can be unpredictable, and how an individual reacts to that unpredictability can be life-altering. Being proactive rather than reactive can mean the difference between life and death. With human papillomavirus (HPV) on the rise, a shift is needed in the way vaccinations are promoted and encouraged. HPV can cause certain cancers later in life that can be prevented now. Dental hygienists and nurses should be ready to take on the role of educating and promoting the HPV vaccine for adolescents, which is the most likely way to decrease these cancers. These health-care professionals have an opportunity to recommend the HPV vaccination while easing concerns and stressing the vaccine’s importance.

Dental hygienists are familiar with many viruses and their possible oral complications. Nurses are familiar with the importance of childhood vaccines that prevent serious viruses and illnesses. An opportunity exists to bring these two professions together to help patients gain a deeper understanding of the possible consequences that HPV can have.

Following the completion of this article, hygienists and nurses will be able to identify barriers that prevent patients from receiving HPV vaccines, discuss the importance of HPV vaccines, and evaluate patient and parent understanding of the vaccine’s importance.

What is HPV?

HPV is the most prevalent sexually communicable infection, and nearly all people will have it at some point.1 The virus is infectious and can present in several places, including hands, feet, genitals, and mouth. Many strains of HPV are harmless, but a few are considered high risk and can cause cancer. Currently, there is no test to determine a person’s HPV status. And, while there is a test for cervical HPV, there is no approved test for oral HPV.1 Research has narrowed HPV types 16 and 18 as being the most dangerous strains, and there are vaccines available to prevent them.

Oropharyngeal cancers (OPC) related to HPV have risen over the last 20 years.2 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics,3 HPV causes 70% of OPC in the US. Many have concluded that the increase in these types of cancers are from the lack of patients receiving HPV vaccinations. Interprofessional work can be incredibly productive in educating patients and parents, which will, in turn, slow the rising numbers of HPV-related cancers.

HVP vaccine

The HPV vaccine can be a confusing situation for parents of vaccine-aged children, and the decision to vaccinate can be nerve-racking with so much information on the internet. Resourceful health-care providers should be available to answer questions and guide parents toward protecting their children from HPV cancers. Pediatricians should be educating parents based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recommendations for both males and females to be vaccinated starting at 11–12 years of age through age 26.4 The vaccine has tested safe and can offer lifelong protection against certain cancers.4

It used to be common practice to teach that HPV caused oral warts. Now, hygienists are learning that there are more than 150 different strains of HPV. Some strains can cause cancers of the mouth, throat, and genitals.5 Dental hygienists should perform a thorough OPC screening for their patients, which includes an oral cancer screening at every appointment. Nurses need to take every opportunity to review vaccination records and educate their patients on the importance of the vaccine when they are in the office. Continuing education classes need to be available for the entire team to update everyone about the newest information on prevention.

Connection to cancer

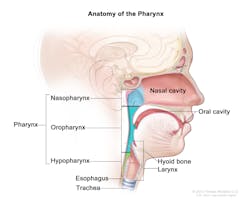

OPCs are usually squamous cell carcinomas.6 These cancers often show up much later in life, many years after the original exposure to HPV, and are usually located in the oropharynx. These cancers often go undetected because the area they occupy is not always visible—e.g., the throat, soft palate, base of the tongue, and tonsils (see Figure 1). Many times, the only symptoms a person may notice resemble a cold or allergies. Receiving a diagnosis can be delayed, making the cancer more advanced once detected.8

Dental hygienists should always use intra- and extraoral palpation in an orderly fashion, feeling for any irregularities, such as sublingual or submandibular swelling, asymmetry, and color or temperature changes.9 Clinicians should also note the size and texture of any abnormalities. Ask open-ended questions to prompt full responses from patients. A referral to an oral surgeon or oral pathologist may be needed.9

Hygienists and nurses should strive to understand barriers that hinder parents from seeking HPV vaccinations for their children. Strongly held beliefs, culture, and language barriers may lead to misinformation about the vaccine’s safety and efficacy. Providers should tactfully and delicately inform patients of the HPV vaccine’s lifelong benefits. Cost may also be a barrier, since the HPV vaccine series is expensive for those without health insurance.

It is important that hygienists and nurses strive to communicate well with their patients to alleviate any barriers to receiving the vaccine. Providers first must understand the patient’s and parent’s knowledge of oral health. The team may need additional training in this regard, such as continuing education in cultural and linguistic competency, patient education, and promotion methods. Providers should know their community. Religious views, socioeconomic status, and language barriers can be overcome. Knowing patients’ ability to understand what is being explained will help providers know how to deliver the information and stress that now is the time to vaccinate—not once patients are sexually active.

As mentioned earlier in this article, the CDC recommends that males and females be vaccinated starting at 11–12 years of age through age 26.4 Providers need to have basic and easy-to-read fact sheets with pictures to send home with patients, videos in the reception area that can educate patients while they wait, and time to add pertinent information to their patients’ medical histories at every appointment. Sometimes parents just need to hear the recommendation a few more times to be convinced of the vaccine’s importance.

The doctor’s encouragement of the HPV vaccine is imperative for a coordinated and cohesive team approach. Without support and correct information, patients and parents may not be motivated to vaccinate, making it impossible to uphold the new routine and further setting back the community back on prevention. It is very important to join professional organizations to help advocate for the vaccination of youth as well as lobbies for health-care funding for the uninsured. It will cost less to prevent HPV-related cancers than to treat them down the road. Speak to school district officials, school nurses, homeschool groups, and other community leaders to spread awareness about the importance of the HPV vaccine.

Vaccinating for HPV is a difficult decision for many parents, due to the myriad of barriers and misinformation. Why is patient education important to dental hygienists and nurses? Both health-care providers are usually the first to see patients, spend the most time gathering medical histories, have an ideal opportunity to earn the trust of patients and parents, and are able to educate and answer questions that may not be asked once the doctor hurries in for the exam. The two professions are about prevention and caring for people. Speak to professional organizations, ask about continuing education on the HPV vaccine, and help your office promote preventive medicine instead of cancer treatment. Compassion, education, and immediate changes are needed to prevent cancer, and dental hygienists and nurses are a great first-line defense.

References

1. Genital HPV infection—fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm. Published 2017. Updated August 20, 2019.

2. Risk factors for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/oral-cavity-and-oropharyngeal-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html. Published 2018. Updated March 9, 2018.

3. Oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) and HPV prevention in children. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/AAP_OPC_HPV_5KeyPoints_Pediatrician_final.pdf. Published 2018.

4. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: What everyone should know. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/public/index.html. Published 2016. Updated November 22, 2016.

5. Horowitz AM, Vamos CA. Preventing HPV-related cancers through immunization. Dimens Dent Hyg. 2019;17(7):36-38,41.

6. NCI staff. HPV vaccination linked to decreased oral HPV infections. National Cancer Institute website. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/hpv-vaccine-oral-infection. Published June 5, 2017.

7. Winslow T. Anatomy of the pharynx [online image]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65972/figure/CDR0000062966__219/. Published 2012.

8. Blair J. Strategies for a new generation of oral cancer patients. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. The ASHA Leader. 2018;23(10):42–44.

9. Burkhart NW. Why palpation is so important: Early detection of oral cancer still depends on correct technique. RDH magazine website. https://www.rdhmag.com/patient-care/article/16409725/why-palpation-is-so-important-early-detection-of-oral-cancer-still-depends-on-correct-technique. Published September 1, 2017.

About the Author

Shannon McCharen, RDH

Shannon McCharen, RDH, has been a dental hygienist for 20 years. She is also a military spouse and has been licensed in five states. McCharen is passionate about improving state legislatures to allow military spouses to continue on with their professional careers without having to take unnecessary tests, and holding licensing boards responsible for carrying out the regulations that are already in place. She holds a part-time job as an adjunct clinical instructor at the local community college while she attends the University of Mississippi Medical Center.