Dental Benefits 2007: We Often Hear What They Don’t Say

Hygienists can no longer continue their same hands-off attitude with regard to insurance codes. As preventive specialists, we must get involved in the coding process.

by Patti DiGangi, RDH, BS

Like many dental hygiene professionals, I suffer from a repetitive motion injury caused by numerous microtraumas over a long career. After diagnosis, the initial treatment was 18 months of physical therapy. Surgery eventually was required, followed by more physical therapy. Many months after the surgery, a cellulitis infection occurred. After resolving the infection, I completed another round of physical therapy. Nearly a year later, a ganglion cyst developed. The orthopedic surgeon ordered another round of physical therapy. I said at the time, “I wonder what my medical benefits will cover.”

“I wonder if my insurance will cover this,” is a statement we often hear from our patients. Unfortunately, upon hearing these words, many dental professionals automatically hear, “I am not going to have that procedure if my insurance doesn’t cover it.” But this is often incorrect. The person didn’t say that. Patients are actually wondering if they have coverage, just as I wondered about coverage for my physical therapy. No aspect of the statement indicates they are absolutely not going to have the proposed care. In my situation, I was thinking about how much my out-of-pocket cost would be, not questioning the care I needed or my doctor’s expertise. I am glad my physician didn’t fall into the same trap dental professionals often do, offering an inappropriate, lesser care based on what I didn’t really say. As dental hygiene professionals, we are in a position to truly make a difference - not just in dental health but whole body health.

Presupposing what a patient says in regard to insurance coverage and performing lesser care is not just inappropriate, it could be life-threatening. Understanding the ever-evolving dental benefits process is critical.

Dental Benefits Are Improving

Last year, the American Heart Association estimated the costs of cardiovascular disease and stroke at $403.1 billion. The American Diabetes Association estimated the cost for diabetes at $132 billion. Cumulative evidence has shown that chronic inflammatory periodontal disease, both gingivitis and periodontitis, are modifiable risk factors for both of these disease processes (Special Supplement to Grand Rounds in Oral-Systemic Medicine, February 2007.) Analysis of current research clearly indicates earlier dental care lowers the risk and severity of these conditions, thus lowering overall medical costs.

Insurance carriers understand this research. Modifications and improvements in coverage include:

- November 2005 Delta Dental of Massachusetts

- Single-tooth implants shown as a scientifically proven treatment

- July 2006 Cigna Dental

- Dental members enrolled in Cigna’s Healthcare Management Program for diabetes and cardiac care may receive 100 percent reimbursement for out-of-pocket costs associated with scaling and root planing (Author’s note: SRP archaic terminology - see below)

- January 2007 Aetna

- Enhanced benefits for pregnant women

- Enhanced benefits for diabetes and coronary artery disease/cerebrovascular disease

- January 2007 Delta Dental of Tennessee

- Diabetes: coverage for four prophylaxes or periodontal maintenance per year

- Pregnancy: coverage for four prophylaxes or periodontal maintenance per year

- Chronic renal failure: coverage for four prophylaxes or periodontal maintenance per year

- Chemotherapy, radiation, organ transplant, or stem cell transplant: coverage for enhanced preventive benefit; e.g., radiation therapy-xerostomia covered for two fluoride treatments per year

~ Author’s note: These are general parameters; individual policies define the boundaries of coverage.

This is the good news. Though the carriers are changing coverage frequency based on up-to-date evidence, the Common Dental Terminology (CDT) process does not yet reflect these same evidence-based changes. Even with the newest version, the confusion and woeful lack of codes adequately describing hygiene care have not changed.

Must Use Most Current CDT Version

Starting Jan. 1, 2007, dental practices were required to begin using the newest version of the CDT book. Have you seen this new version? What might stand out immediately is that the name of the book has changed. Since 1991, we have had versions CDT-1 through CDT-5. The newest version is now time-stamped in its name - CDT 2007-2008. In our quickly evolving world, insurance codes and interpretations are constantly changing. This newest version is time-sensitive and will become obsolete Jan. 1, 2009. Practices and practitioners alike need to be aware of the new, changed and deleted codes by using the most current version.

As pointed out in two articles in RDH magazine last year (May and June 2006), whether you like it or not - or want to be involved or not - your practice most likely accepts insurance assignment or is enrolled in PPOs/HMOs. You, as a clinician, are affected by the dental benefits industry. Dental insurance is a marketplace reality, yet many hygienists take a complete hands-off attitude to something affecting much of what we do. Insurance carriers are often perceived as the bad guys and inappropriately blamed. Before any discussion of how insurance affects hygiene, it is once again necessary to clarify and remind practitioners that we are treating patients, not insurance policies. Treatment plans should be developed according to professional standards - not according to contract provisions.

Standard of Care

Reviewing the history of the coding process can help practitioners understand how codes for CDT 2007-2008 were created, deleted, or revised. Before the advent of dental benefits, dentistry was a fee-for-service profession. In the 1960s, insurance carriers began offering a wide variety of policies. Each carrier had its own form and unique set of codes. Many different tooth-numbering systems were still in use. By 1986, the American Dental Association decided it was time to take the confusion out of this process. The Council on Dental Benefits elected to develop an educational manual. The goals for the first book were:

- Act as educational resource

- Serve as a basic guide when administering dental claims

- Communicate accurate information

- Leave no room for interpretation (Author’s note: this one hasn’t worked out to well so far)

- Provide standard to document procedures

The meaning of the word standard is important in understanding the CDT process. Standard of care is a phrase that seems to have different meanings to different people. A wide array of information comprises our standard of care. One malpractice carrier defined standard of care this way:

“The standard of care is a relative standard, not a strict legal prescription. It is based on the actions of the reasonable person of ordinary prudence. Since the conduct of a reasonable person varies with the situation he or she is confronted with, negligence is, therefore, defined as the failure to do what this reasonable person would do under the same or similar circumstances. The standard represents the minimum level of conduct (author emphasis) below which members of society must not fall. Persons with higher level of knowledge, skill, intelligence, such dental health professionals, are held to a correspondingly higher standard. The conduct of the dental health professional will be judged by the conduct of other dental health professionals practicing under the same or similar circumstances.”

In litigation, attorneys look to professional associations - both the ADA and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association - when seeking the definition of the standard of care. In the ADA’s Principle of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct, there is a section with advisory opinions in regard to dental benefits. These opinions contribute to the standard of care.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) was created to improve portability and continuity of health insurance to combat waste, fraud, and abuse in health insurance and health-care delivery. Under HIPAA, code sets for medical data are required for data elements in the administrative and financial health-care transactions. A code set is any set of codes used for encoding data elements, such as tables of terms, medical concepts, medical diagnosis codes, or medical procedure codes. On Aug. 17, 2000, HIPAA named CDT as the standard code set for dentistry. Because HIPAA designates CDT as the national standard code set, CDT can be considered part of the standard of care, making a complete awareness and understanding of the codes imperative.

Code Revision Committee

Requests for changes to CDT can come from members of the profession, third-party payer organizations, and other interested parties. Review of and action on requested changes takes place during the Code Revision Committee’s (CRC) periodic meetings. The CRC is comprised of equal representation from third-party payers and the ADA. Six third-party payer organizations are represented:

- America’s Health Insurance Plans

- Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- Delta Dental Plans Association

- National Association of Dental Plans

- National Purchaser of Dental Benefits.

The dental profession is represented by six practicing dentists appointed by the president of the ADA. Other professional groups or individuals may submit changes. This change process is highly scheduled and specific. Changes for CDT 2009-2010 will be considered during the CRC’s next meeting in August 2007. Opinions on changes to be discussed had to be submitted by April 1, 2007. This is already the second meeting on CDT 2009-2010. The best resource on timelines and information about suggesting a change can be found on the ADA’s Web site at http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/cdt/change.asp.

CDT 2007-2008 Changes and Addition in Evaluation Codes

The clinical oral evaluation section underwent several important changes and one addition. As was pointed out in “Alternating Insurance Codes” (RDH, June 2006), a practitioner needs to be aware that these codes are evaluation codes, not exam codes. The difference is that an evaluation includes a diagnosis and treatment plan, it is not enough to simply gather data.

Codes D0150 Comprehensive Oral Evaluation, D0120 Periodic Oral Evaluation, and D0180 Comprehensive Oral Evaluation have all been altered to include specific language on oral cancer evaluation. The CRC report stated the reason for this change:

“Expansion of language to include oral cancer evaluation based on growing awareness of change needed to reduce morbidity and mortality of oral cancer.”

Because this language is built in to the codes, submitting these codes without performing an oral cancer evaluation could constitute fraud. The only way to demonstrate that the evaluation was performed is complete, appropriate documentation.

A new evaluation code was added, the D0145 Oral evaluation for a patient under 3 years of age and counseling with primary caregiver. The descriptor is “Diagnostic and preventive services performed for a child under the age of three preferably within the first six months of the eruption of the first primary tooth, including recording the oral and physical health history, evaluation of caries susceptibility, development of an appropriate preventive oral health regimen, and communication with and counseling of the child’s parent, legal guardian, and/or primary caregiver.” This new code has considerably more words to define it, possibly in attempt to reduce the confusion in finding the correct code.

CDT 2007-2008 Changes In Radiographic Codes

In my courses, hygienists get riled up when we discuss radiographic guidelines and coverage. A new code for D0273 Bite Wing added three films, which seems fairly insignificant. Of greater significance, insurance carriers are making changes in the frequency of coverage for radiographs.

What many practitioners have still not embraced are the Updated Guidelines for Radiographs that the ADA released in conjunction with the Food and Drug Administration in January 2005. An important portion of these guidelines state:

“Radiographic screening for the purpose of detecting disease before clinical examination should not be performed. A thorough clinical examination, consideration of the patient history, review of any prior radiographs, caries risk assessment, and consideration of both the dental and general health needs of the patient should precede radiographic examination.”

There has never been a code for taking X-rays only. You must have a specific reason for taking radiographs and include interpretation. Your records must document 1) what is being looked for and the reason for the radiograph, and 2) what was found.

RDH author Carol Tekavec said in Dental Economics (March 2005), that radiographic benefits must be for diagnostic purposes. If the radiographs taken provide no adjunctive support, they are not considered reimbursable. Without appropriate documentation, claims for radiographs may not be paid. With utilization review, benefits already reimbursed may need to be returned. Gone are the days of taking radiographs simply by the “calendar.” The passage of a certain time frame - i.e., one year - does not necessarily warrant taking radiographs.

Based on these guidelines and the body of evidence used to create them, as of Jan. 1, 2007, Delta Dental created these radiographic coverage parameters based on risk:

- Low risk for caries -

- 12 to 24 months for children

- 18 to 24 months for adolescents

- 24 to 36 months for adults

- High risk for caries -

- Two or more restorations in 12 months

- six to 18 months

(Please don’t shoot the messenger.)

CDT 2007-2008 Changes and Addition In Fluoride

In CDT-4 in 2003, questions arose as to the type of fluoride that constitutes a fluoride treatment. CRC clarified this:

“Prescription-strength fluoride product designed solely for use in the dental office, delivered to the dentition under the direct supervision of a dental professional. Fluoride must be applied separately from prophylaxis paste.”

CDT 2007-2007 eliminated the combination prophylaxis and fluoride codes, D1201 Topical Fluoride including prophylaxis child and D1205 Topical Fluoride including prophylaxis adult.

A new code was added, D1206 topical fluoride varnish, therapeutic application for moderate to high caries risk. It is important to note the descriptor:

“Application of topical fluoride varnish, delivered at a single visit and involving the entire oral cavity.”

Therefore, this is not a code for a single tooth. Further, the question and answer section of CDT states that this new code is not for desensitizing. D9910 code is the appropriate desensitizing code. The CRC reports the reason for the addition of this code:

“Fluoride varnish application has been found to be an efficacious procedure. Since fluoride varnish may need to be applied more frequently than a gel or rinse, the committee approved the new code to differentiate this delivery technique.”

Existence of a code doesn’t mean there is coverage under a policy. Often new codes are not covered under current policies because the code did not exist at the time the policy was written.

CDT 2007-2008 Changes In Prophylaxis and Periodontal Codes

Codes D1110 Adult Prophylaxis and D1120 Child Prophylaxis have been redefined so many times, rendering them nearly useless. Complete elimination of these codes seems most appropriate. When the CDT system was initially developed in the late 1980s, the codes were purposely written to allow for additions. There are plenty of unused numbers available for a new system that better supports our current understanding of the oral-systemic connections and the preventive and therapeutic care provided by hygienists.

There were no changes made in the prophylaxis code. The explanation was:

“CRC representatives acknowledged that the current nomenclature and descriptors for both prophylaxis codes are confusing; however, the committee elected not to change the current code structure.”

The CRC seems to agree about the confusion but, unfortunately, chose not to make the definitions clearer.

Even though there is still considerable confusion about D4355 Full Mouth Debridement to Enable Comprehensive Evaluation and Diagnosis and D4910 Periodontal Maintenance, the CRC also made no changes. Nor were changes made in D4341 Periodontal Scaling and Root Planing’s four or more teeth per quadrant or D4342 Periodontal Scaling and Root Planing’s one to three teeth per quadrant. The current understanding of periodontal disease and evidence does not support the name of the code or portion of the descriptions stating:

“Root planing is the definitive procedure designed for the removal of cementum and dentin that is rough and/or permeated by calculus or contaminated with toxins or microorganisms.”

This statement is based on the pre-1960s calculus theory of periodontal disease, giving credence to a statement made by the Dr. Robert Compton, chief dental officer for Delta Dental Massachusetts: “Almost all dental benefits are based on procedures developed in the 1950s.”

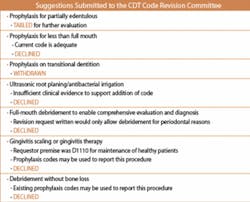

Many others agree with these thoughts and offered changes for CDT 2007-2008. Some of these suggestions and the decisions of the CRC per their reports are shown in Table 1. As you read them, you probably think these suggestions have a great deal of merit. The CRC apparently thought and voted otherwise.

Hygienists Must Step Up To Make a Difference

In 2004, there were 36.3 million people in the United States age 65 and older, with 64,658 people age 100 or older. By 2030, it is estimated that 71.5 million people in the United States will be over age 65. People are living longer and keeping their teeth longer, but with advancing age, they often have more health problems and take more medications. This creates higher risk and greater cost. Our entire health-care system could collapse under this weight. Chronic inflammatory periodontal disease, both gingivitis and periodontitis, are modifiable risk factors. How oral health is managed can make a major difference in its overall cost. Earlier dental care lowered the risk and severity of these conditions, lowering overall medical costs. The CRC needs to make changes based on current evidence rather than 1950s thinking. Hygienists can no longer continue their same hands-off attitude with regard to insurance codes. As preventive specialists, we must get involved in the coding process.

About the Author

Patti DiGangi, RDH, BS, is a speaker, author, practicing dental hygiene clinician, and American Red Cross authorized provider of CPR and first aid training. She can be contacted through her Web site at www.pdigangi.com.