Minimal Intervention

Glass Ionomers, Mystery or Mastery: Part 3

The glass ionomer wasn't dead; it was just misunderstood. Researchers modified its basis for success in minimal intervention dental hygiene.

by Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH

Dental materials are not usually a topic dental hygienists like to sit around and talk about. With a few exceptions, dental hygienists don't know much about dental materials. Amalgams are gray, composites or resins are white, porcelain is white, and sealants are … what are sealants? They're white, sure, but what are they really? Why have an article titled, "Glass Ionomers" when we talk about sealants?

In the beginning sealants were either white or clear, they were filled or not, and they were self-curing or light cured. To tell if sealants were working, clinicians just looked. If they were present, they were working.

Glass ionomers entered the market more than a decade ago. The material made its debut as an alternative to amalgam because it was white. It lacked a fundamental quality of a good dental material — strength. Glass ionomers have always worn quickly, and the dental community lost faith in it, even though it released fluoride into the adjacent environment, even though recurrent decay was almost never a problem, and even though the type of biofilm that grew on the material was markedly different from the regular biofilm. If the dentist had to replace it too often, say annually or so, it wasn't worth it.

Researchers, though, kept looking for a solution. They found that, by making a few modifications to the basic formula, glass ionomer could be used as a sealant. But early tests didn't show promise. A literature review revealed a lot of promising reviews supporting regular resin sealants over glass ionomer. Over and over again the researchers' disappointment seeped from the pages of the paper, because glass ionomer sealant failed, and it was no longer visible.

A sentence read something like, "Recurrent decay occurred in X teeth with the resin sealant and a tiny fraction of X teeth with the glass ionomers." The glass ionomer wasn't dead, it was just misunderstood. The basis for success had to be modified. A new question formed: Is it more important that the sealant is present, or that the tooth doesn"t succumb to the bacterial infection?

Further research with scanning electron microscopy found that, although invisible to the unaided though trained eye, the material is still there. Much of minimal intervention dental hygiene is happening at a place that is invisible to the naked eye.

Glass ionomers are vital materials. They release fluoride, and they also recharge with fluoride every time it is in the vicinity. Toothpaste, fluoride varnish, fluoride rinses, and fluoride in the water all recharge glass ionomers, even if we can no longer see them. The reason we can"t see them is because of the way they attach to the teeth.

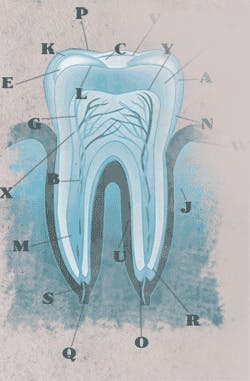

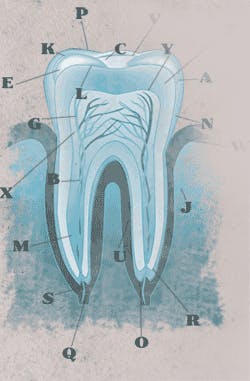

Resin material must attach to the tooth mechanically. That means an etchant must be applied to the tooth, and the etchant dissolves part of the enamel and creates tiny retention pegs. The resin is flowed onto the pegs and cured, and if the pegs are disturbed before the material is cured, the retention of the material is compromised. Saliva contamination and improper tooth preparation are two of the most common problems affecting sealant retention.

Glass ionomers, on the other hand, attach by fusing into the enamel. The material has a low pH that allows it to seep into the enamel, and it does this in the presence of moisture. A dry tooth is detrimental to bonding. This fusion is permanent. One researcher boldly said that the tensile strength of a glass ionomer has never been measured because no one has been able to get it off the tooth. Visible or not, it"s there, and it acts as a physical barrier against biofilm destruction and still recharges with fluoride and releases it into the adjacent enamel.

Benefits of glass ionomer attachment mechanism include the ability to attach to any surface of the tooth. Glass ionomer sealant material is not as viscous as its partner restorative material, so it can be placed on the buccal of the molars in a person with a disability, protecting the tooth. It will act as a physical barrier as well as a fluoride battery to the tooth.

Saying that biofilms don"t grow on glass ionomers may be an overstatement. A biofilm on a glass ionomer has different characteristics, most notably, the inability of strep mutans to grow on it effectively.

A toxic biofilm is necessary to the caries process. A toxic biofilm in this context is one that contains streptococcus mutans and has a low pH. The biofilm that accumulates on a glass ionomer is high in basophilic bacteria. This shift, when multiplied across many surfaces in the mouth, can make the mouth healthier.

Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) is where soft decayed material is removed with hand instruments and the tooth is repaired, or at least the hole filled, with glass ionomer. This technique has been studied across the globe and findings show retention that mimics definitive restorations with rotary instruments. ART can decrease the oral bacterial load in residents of long-term care with frank decay, and discourage secondary caries by remembering that one and two surface fillings can last up to five years. Newer glass ionomer materials containing chlorhexidine have been showing promise, too.

Glass ionomers have a place in dental hygiene. As a sealant or surface protectant, the master dental hygienist can affect the oral health of people without expecting them to brush their teeth to dental hygiene perfection.

PubMed search strings:

Caries, glass ionomer

Glass ionomer, ART

Glass ionomer, biofilm

About the Author

Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH, FACE, is a practicing dental hygienist from Sun Prairie, WI. The Purple Guide: Developing Your Clinical Dental Hygiene Career is available at www.rdhpurpleguide.com by Gutkowski and Nieves. An international speaker and award winning writer, Gutkowski can be reached at [email protected].

Where To Use Glass Ionomer Materials:

- High caries risk children as traditional sealant placement

- High caries risk adults with cognitive or physical limitations to oral cleanliness

- Dependent adults to protect teeth

- Frank caries lesions of dependent adults or children (ART)