Central Giant Cell Granuloma: Aggressive lesion can cause jaw to swell, and loosen teeth

Aggressive lesion can cause jaw to swell, and loosen teeth

NANCY W. BURKHART

The central giant cell granuloma (CGCG) is considered a benign, nonneoplastic lesion of bone found in a younger age group who are usually less than 30 years of age. The more aggressive type may cause root divergence and destruction of the surrounding bone that expand the cortical plate.

Usually discovered through a radiograph depicting a radiolucent lesion of the mandible or maxilla, the CGCG accounts for fewer than 7% of all benign tumors of the jaws-with a prevalence for the mandible at a 65 to 75% rate and affecting females more often than males. The growth is an intraosseous lesion consisting of cellular fibrous tissue (fibroblasts) that contains multinucleated giant cells. The CGCG is very slow growing. But, when seen in a more aggressive form, it exhibits rapid growth, swelling, loosening of the teeth, displacement of the teeth, and it penetrates the cortical bone (see Figure 1).

Etiology: At one time, these lesions were known as "giant cell reparative granulomas" because it was thought that there was a reparative component to the growths. However, the true etiology is unknown and still controversial. The evidence is not available to classify the lesions as reparative. The CGCG is thought by many to be reactive, but it is classified as a benign, nonneoplastic lesion.

Figure 1

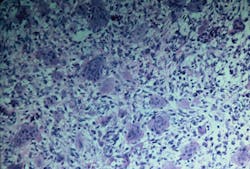

Figure 2

Photos Source: DeLong L, Burkhart NW. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 2013; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

There is also debate on whether the most aggressive types may fall into a neoplasm category. One other recent explanation by Venkateshwarlu et al. (2010) states that the female predilection (2:1 ratio) to this type of lesion may possibly be explained with normal hormonal secretion. Another observation is that in young children, the craniofacial skeleton is actively developing to include osteogenesis, exfoliation, and eruption of teeth. Since these processes cease in adulthood, Venkateshwarlu states that younger individuals may be more predisposed to this type of lesion.

Epidemiology: Most CGCG found in the oral tissue and bone are nonaggressive and very slow growing, usually affecting the anterior mandible and maxilla. The lesions are known to occur in children and young adults with a female predilection. About 30% are found to be in a more aggressive state and exhibit rapid growth.

Radiographic characteristics: The CGCG is seen as a multilocular lesion or, in rare cases, a unilocular lesion that has well-defined margins. The borders may have a scalloped appearance. The more aggressive form may depict not only root resorption but also perforation of cortical bone.

Perioral and intraoral characteristics: The CGCG are usually painless unless the size and expansion of the lesion becomes excessive. Found primarily anterior to the first molar, radiographic appearances may be noted because of the divergence and expanding margins of a radiolucent lesion. Loss of the lamina dura may be an early indication. Pain along with a noted clinical appearance is usually seen when the lesion penetrates and protrudes through the cortical bone, but not reported initially. The CGCG then may be noted as a soft tissue, flat-based nodule with a blue-to-purple color when this stage of development is obtained.

Distinguishing characteristics: The CGCG is usually slow growing, nonaggressive, and asymptomatic. In some cases, though, it may be more aggressive with bone destruction, tooth displacement, and pain. The expansion of bone is certainly a key feature with this lesion. The lesion usually occurs in the mandible and anterior to the first molars.

Significant microscopic characteristics: CGCG is noted for the many multinucleated giant cells that are found within the tissue specimen. The multinucleated giant cells are within a sea of spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells and found in areas of hemorrhage.

The giant cells may vary in size and number with scattered placement, or they may be concentrated within distinct areas of the specimen. Newly formed bone may be present within the specimen as well. The more aggressive type of CGCG is not distinguishable from the nonaggressive type by microscopic examination (see Figure 2).

Dental implications: Aggressive lesions may occur, and the CGCG may recur as well, even when thoroughly removed initially. The brown tumor is found in patients who have hyperparathyroidism and has a similar appearance but dissipates when hyperparathyroidism is under control. Surgery is not indicated when a brown tumor is diagnosed. In the more aggressive forms of CGCG, dramatic jaw swelling may occur and there may be loosening of the teeth in the area of the lesion.

Possible differential diagnosis:

Hyperparathyroidism (brown tumor)

Cherubism

Giant cell tumors involving Paget disease

Aneurysmal bone cysts

Ameloblastoma

Odontogenic keratocyst

Treatment and prognosis: The prognosis is good when complete removal is obtained, and excision by curettage with removal of peripheral bone margins is optimal. Early intervention and treatment will produce a better outcome for the patient.

A recurrence rate of 15-20% is noted. The more aggressive lesions tend to have a higher recurrence rate. Those occurring in children may also have a higher rate of occurrence and may have a less favorable outcome with the more aggressive types of lesions.

In the aggressive forms, recent reports (Tarsitano et al. 2015) of the use of surgical enucleation with subcutaneous injection of Interferon-alpha-2a proved to be successful in follow-up studies with no recurrence after eight years. Treatment with immunomodulary drugs and calcitonin are sometimes effective depending upon the type of CGCG.

As always, keep asking good questions and continue to listen to your patients. RDH

CGCG from an oral medicine perspective

• Close follow-up of the patient is recommended because of the tendency for the CGCG to recur. This is especially relevant in the more aggressive forms.

• In the case of children, educating the parent on what factors one would observe in a recurrence is beneficial.

• Written patient education is always welcome.

• Patients tend to move to different parts of the world, and the continuity of care is often lacking in society today because of transient lifestyles.

• Since these lesions do not usually cause discomfort, any noted changes should be reported such as pain, loss of sensation, or divergence of teeth in that localized area and these factors would warrant a timely evaluation.

• Providing a new clinician/health-care provider with past reports is needed as well.

• Teaching parents of children with any type of risk factors on how to perform an oral exam is beneficial. Adults should learn how to perform an oral cancer screening as well.

References

1. Krishnappa S, Srinath S, Gopinath P, Krishnappa VS. Central giant cell granuloma in a 4-year-old female child. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2015; 33:337-40. Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 2003 4th edition, Saunders, St. Louis, Missouri.

2. Tarsitano A, Del Corso G, Pizzigallo A, Marchetti C. Aggressive central giant cell granuloma of the mandible treated with conservative surgical enucleation and Interferon-a-2a: Complete remission with long-term follow-up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015 May 7.Pii: So278-2391 (15)00488-7.Doi 10.1016/j.joms.2015.04.029.

3. Venkateshwarlu M, Geetha P, Radhika B. Central giant cell granuloma. IJDA, 2010; 2(1); 134-137.

NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics/stomatology, Baylor College of Dentistry and the Texas A & M Health Science Center, Dallas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (http://bcd.tamhsc.edu/olp/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. She was a 2006 Crest/ADHA award winner. She is a 2012 Mentor of Distinction through Philips Oral Healthcare and PennWell Corp. Her website for seminars on mucosal diseases, oral cancer, and oral pathology topics is www.nancywburkhart.com. She can be contacted at [email protected].