A-hunting she will go

Hygiene + Hunting = How to make Julia Egan happy

by Cathy Hester Seckman, RDH

Some people think cleaning teeth is a disgusting thing to do, but others think it's fun, intriguing, and interesting. They can get downright passionate about it.

So how do you feel about hunting? Here's a hygienist who thinks it's fun, intriguing, and interesting. She can get downright passionate about it.

Julia Egan, of Honor, Mich., had always been around guns and liked to shoot, but she had never tried hunting until she moved to the northern part of lower Michigan after college. She earned an associate's degree from Lansing Community College and a bachelor's degree in biology from Michigan State University in 1981.

"A lot of women hunt in this area, and it seems like all the guys do. It's an activity to share with your spouse. I literally moved up here from the city with 30 pairs of high heels. Well, out they went. I bought a pair of hiking boots, got a rifle, and learned to track. I started out bow-hunting for deer."

She didn't try bird hunting until a patient suggested it three years ago. Julia has worked for Dr. Jessica Rickert in Interlochen, Mich., for 18 years, and considers many of the patients part of her extended family. So when Amy Luther invited her to go pheasant hunting, she was happy to try it.

"There was Amy, four months pregnant, with her one-year-old on her back, out in the field with a loaded gun. It was amazing." Amy and her husband, Mike, own the 32,000-acre Luther's Big Game Hunting Preserve.

Julia had a great time. Not only did she discover a new hobby, she also met guide Bob Parkhill (Parks), who would become her very significant other.

"Parks has taught me everything I know about bird hunting and dogs," she says. "I never even knew I wanted a dog; I've always thought I was a cat person. It took awhile to get used to dogs and dog hair and all that."

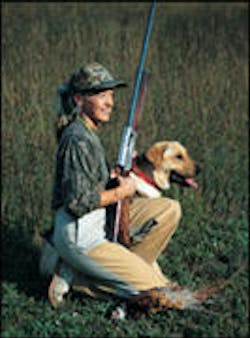

Julia and her yellow Labrador retriever, Cali, spend most of their time at Bear Creek, Parks' 80-acre spread south of Interlochen. Cali survived a bout with lupus early in her life, but after $4,000-$5,000 in treatment, she has recovered and is able to hunt. Also at Bear Creek are Parks' dogs, a yellow Lab named Dakota and three German short-haired pointers, Kat, Gidget, and Abby.

"As part of the pack family," Julia says, "I do most of the feeding, bathing, nurturing, healing, and scheduling. Parks does most of the discipline, and we share training and conditioning responsibilities."

The five dogs, Julia, and Parks work together as guides for bird hunting in the wild or on preserves.

"I work three 10-hour days as a hygienist," Julia explains, "Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday. That gives me four days off every week, and Parks is retired, so people can book us for hunts on weekends. We have good dogs, bred for nose and temperament, that are whistle-trained, and on hot days we can rotate among the five dogs."

For a hunt on a preserve, the hunters buy farm-raised pheasants, for instance, at $8 to $10 per bird. The birds are released in a field three hours before the hunt. Julia and Parks then line up their dogs and hunters at the edge of a field and set off at a slow walk. The pointers are out front, quartering for birds. They point; the retrievers flush the birds into flight; the hunters shoot; and the dogs bring back the game.

"After four hours we might have 60 birds when the hunters have only paid for 50 releases. That's how good our dogs are. We lay out the take, get pictures, the dogs are happy, and we're exhausted."

The next question, of course, is obvious. Who cleans those 60 birds? Is it Julia, the hygienist, who should be used to ... um ... disgusting stuff?

"The clients don't clean their own kill, but there's usually a charge for the service. I was introduced to the art of field dressing and cleaning three years ago when I shot my first wild turkey. Yes, I know how, but I get out of it as often as I can, usually by volunteering to prepare the feast. And that works almost every time!

"When I cleaned that first turkey, I hated it, and I hated the guys for making me do it. But after a few birds, it's just like hygiene. You get used to it, and it is no longer disgusting; it's just another thing that has to be done ... although I admit that field dressing a gut-shot deer is very difficult for the weak of stomach — now that's truly disgusting."

Hunters don't wear gloves, she reports. "You just have lots of blood and feathers that stick to everything, so getting out of it is always good."

Julia and Parks also guide private hunts on Drummond Island, Mich., some in the wild and some on preserves. Grouse, duck, woodcock, pheasant, and quail are among their prey. In Winner, S.D., the pair lease a 6,000-acre upland farm where they hunt wild pheasant, sharp-tailed grouse, Hungarian partridge, and prairie chickens in the fall.

"There are no released birds out there. It's more challenging to hunt wild birds, because they behave very differently than farm-raised birds. Sometimes it's more frustrating, but most of the time it's more fun and a good way to hone your shooting skills."

Besides hunting, Julia's hobbies include cooking, travel, reading, gardening, and "paying someone else to clean my house so I have time for the fun things in life." She also enjoys skeet shooting and golf, but has had to give up both recently because of elbow surgery. "For a while," she says, "I thought I wouldn't be able to go back to work, but I did. Now I save everything I have for my three days of hygiene. By Wednesday, my arm is throbbing, and I have to ice it down at night.

"But I'd still rather do hygiene than anything. I always say if I won the lottery, I'd still work for Jessica for free. She's been amazing. She treats me like a partner instead of an employee. We've been through hard times together. We started out with one operatory, which we shared, and now we have five operatories and a staff of 10. Jessica has inspired and empowered me to continue to grow and learn in my dental hygiene career.

"Dental hygiene has been very good to me and for me. It has taught me to see inside people, to listen, to care, to help, and to inspire — to make a friend today and secure a patient for a lifetime. Getting the calculus off the distal of No. 3 is important, but sometimes you have to lay the clipboard down, set aside the instruments, take off the mask, and spend five or 10 minutes listening, asking questions, empathizing, and understanding. You have to let patients know you care about them as a person, not just as a mouth in the chair. This has been the stronghold of my practice, and it is reflected back to me by my patients' loyalty."

Between a satisfying career, a challenging hobby, and a partner who shares her passions, Julia is perfectly content. "I love my life. I wouldn't trade this lifestyle for anything."

Cathy Hester Seckman, RDH, is a frequent contributor who is based in Calcutta, Ohio.