Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (focal lymphoid hyperplasia)

Nancy W. Burkhart, EdD, BSDH, AFAAOM

When we think of hyperplasia, we think of excessive tissue growth. When we think of lymphoid hyperplasia in the oral cavity, we often think of localized increases of lymph node tissue. Our attention is especially drawn to areas where increased gingival growth is uncommon, such as the soft palate, uvula, and posterior oropharynx. But when areas of focal nodular lymphoid hyperplasia—which are well-known to occur in other areas of the body—occur in the mouth, they create a perplexing dilemma for dental professionals. This is because reactive growth of lymphoid tissue can be difficult to distinguish from the most serious neoplastic lesions.1

Understanding reactive growth

Aggregates of lymphoid tissue are all over the oral mucosa, but they are often prominent in the soft palate, uvula, and pharynx. These lymphoid tissues are controlled by specialized cells that arm themselves to attack and destroy foreign invaders—such as bacteria, fungi, or viruses—through phagocytosis or the production of antibodies. Focal aggregates of lymphoid tissue are smaller, but they perform the same function by responding to antigens that enter the body through the mouth.

Like all lymphoid tissue in the body, oral lymphoid tissue is highly reactive and can enlarge from time to time as it “reacts” to foreign entities. As they mount an immune response, lymphoid cells can proliferate and enlarge. The term reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) is used as a general term to describe these types of lymphoid proliferations.

In the orofacial region, RLH most often occurs in the oropharynx, Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring, the soft palate, the lateral tongue, and the floor of the mouth.2 Waldeyer’s ring includes the lingual and palatine tonsils, the adenoids, lymphoid follicles located on the posterolateral tongue in the area of the foliate papillae, and level 1 lymph nodes in the floor of the mouth.

Visualizing RLH

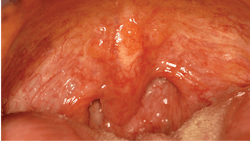

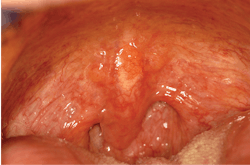

As seen in Figure 1, the soft palate, uvula, and posterior pharynx demonstrate multiple areas of enlargement that are consistent with lymphoid tissue. Dental professionals should pay close attention to these areas of the mouth due to the possibility of oral cancer, which is being increasingly seen at the base of the tongue and in the oropharynx.

In the literature, findings of RLH are well-documented. Reported cases involve the conjunctiva, liver, gastrointestinal tract, stomach, lungs, paranasal sinuses, and many cutaneous areas. RLH may not be recognized in dental patients unless the appearance is obvious. When oral aggregates appear in clusters or have an unusual appearance or enlargement, clinicians may question whether abnormalities are present. In addition, patients may notice irregularities on their own, thereby bringing the appearance to the attention of their dentists or hygienists. Clinical images of entities may be beneficial for documentation purposes, as they may be viewed during future appointments should there be recurrences.

Depending upon the location of the RLH, the appearance of tissue may vary. When the lymphoid tissue is deeply seated, the appearance may be more pink or deeper in color. When on the surface tissue, there may be a yellow, white, or even vesicular appearance, as seen in Figure 1.RLH histology

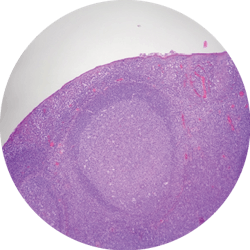

A lymphoid follicle under microscope is shown in Figure 2. The tissue demonstrates a “polarized” mantle zone beneath a somewhat attenuated epithelium. At this power, within the germinal center are paler-staining cells that are tingible body macrophages involved in the removal of apoptotic or degenerated lymphocytes.

Figure 2 shows the process of a reactive lymphoid lesion histologically. It provides context as to what an oral pathologist might see that aides in excludingnonreactive or neoplastic lesions.

Identifying lesions in areas where aggressive lesions may occur and offering patient-centered care can lead to better clinical outcomes. As always, continue to ask good questions and listen to what your patients are telling you!References

1. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016.

2. Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017.

Nancy W. Burkhart, EdD, BSDH, AFAAOM, is an adjunct associate professor in the Department of Periodontics-Stomatology, College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University, Dallas, Texas. She is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (dentistry.tamhsc.edu/olp) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist, now in its third edition. Dr. Burkhart was awarded an affiliate fellow status in the American Academy of Oral Medicine in 2016. She was awarded the Dental Professional of the Year in 2017 through the International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Foundation and is a 2017 Sunstar/RDH Award of Distinction recipient. She can be contacted at [email protected].