Editor's note: Staff Rx appears monthly in RDH magazine. View Watterson's past columns here.

Dear Dianne,

We see many periodontal patients in our general practice—from mild to severe cases. Sometimes, the more advanced cases have purulent drainage and refuse to see a periodontist. This puts me in a difficult position, because I know that without specialized care, these patients will likely lose more teeth.

The doctor I work with is great, but he is very reluctant to dismiss people from the practice. I’m wondering if a round of systemic antibiotics might be appropriate for some of these periodontal patients. What is the current thinking about using systemic antibiotics for periodontal infections? Also, what other strategies would you use for periodontal patients who refuse to go to a periodontist?

Kelly, RDH

Dear Kelly,

Thanks for asking such a great question. Many hygienists are faced with the dilemma of how to proceed when periodontal patients refuse to see a periodontist. Fortunately, there are some treatment options.

Your question concerns the use of systemic antibiotics for certain periodontal patients. My clinical experience is that most periodontal patients we treat do not need a systemic antibiotic, but I also believe that there are some who will not get better without them.

A very good literature review of this subject was published by Herrera et al.1 in 2008 in the Journal of Clinical Periodontology. Titled “Antimicrobial therapy in periodontitis: The use of systemic antimicrobials against the subgingival biofilm,” this review found that: (1) systemic antibiotics as a monotherapy are not effective in treating periodontal infections but should be used in conjunction with definitive debridement therapy; (2) antibiotics should be commenced at the completion of debridement therapy; (3) debridement should be completed in a short time; i.e., a week or less; and (4) the debridement should be of adequate quality to optimize the results.1

An earlier study by Kornman et al.2 found that excellent supragingival plaque control was an essential factor necessary to achieve superior clinical outcomes when using systemic antibiotic therapy in periodontitis patients. So, if a patient is not compliant with practicing excellent home care, antibiotics will not be helpful.

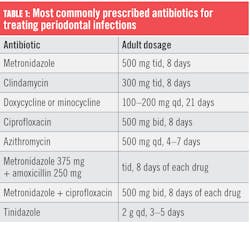

The American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) published a position paper regarding the use of adjunctive systemic antibiotics.3 The AAP position is that “prime candidates for systemic antibiotic therapy are patients who exhibit continuing loss of periodontal attachment despite diligent conventional mechanical periodontal therapy.”3 Antibiotics are also indicated for patients with acute or severe periodontal infections or patients with aggressive forms of periodontitis. See Table 1 for a list of common antibiotics used to treat periodontal infections.The last antibiotic listed, tinidazole, is the latest antibiotic to be found effective in treating some periodontal infections. Tinidazole is an antibiotic/antiprotozoal/antiamoebic drug. Tinidazole is also used to treat certain types of vaginal infections (bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis).

Rams et al.4 wrote, “Tinidazole performed in vitro similar to metronidazole, and markedly better than amoxicillin, doxycycline, or clindamycin, against fresh clinical isolates of red/orange complex periodontal pathogens. As a result of its similar antimicrobial spectrum, and more convenient once-a-day oral dosing, tinidazole should be considered in place of metronidazole for systemic periodontitis drug therapy.”

Since periodontal infections are microbial in nature, it seems logical that an appropriate systemic antibiotic might benefit certain patients. But how can a clinician know which one (or which combination) would be the most appropriate? Given the inherent dangers of antibiotic overuse and the problems of resistance and reactions, it seems prudent to determine the patient’s microbial profile before prescribing. The best way would be to do a microbial analysis, which involves obtaining a sample of the patient’s plaque and sending it to a lab for analysis.

One option is MicrobeLinkDx. The plaque sample is obtained using paper points, which are then inserted into a vial and mailed to the lab. DNA-PCR detection analysis is used, which means the microbes do not have to be alive. (For more information, visit MicrobeLinkDx.com or call (866) 756-4246.)

Live-microbe testing is available through the Oral Microbiology Testing Service (OMTS) at Temple University. (For information about OMTS laboratory services and fees, microbial sampling and shipping instructions, and obtaining a free test sampling kit, contact Jacqueline Sautter at (215) 707-4237.)

There are three primary reasons antibiotics may not work. First, the patient may take it incorrectly. Second, the patient may not finish the entire round of antibiotic. Third, the wrong antibiotic may have been given.

These are the essential elements for successful periodontal antibiotic therapy:

- Obtain comprehensive microbiological analysis.

- Review patient medical status.

- Consider potential adverse side effects and drug interactions.

- Complete whole-mouth mechanical root scaling before instituting antibiotics.

- Train patient in home plaque control regimen.

- Check patient compliance with taking the prescribed antibiotic drug regimen.

There are many reasons that patients refuse treatment recommendations and referrals, including financial constraints, inconvenience, fear, and lack of trust. Anytime a patient refuses definitive care of periodontal problems, there must be a discussion with the patient about the ramifications of nontreatment. Be sure to obtain the patient’s signature on a “Refusal of Treatment Recommendation” document that becomes a part of the patient record. (Contact me by email, and I will send you a sample document.)

If the doctor chooses to retain the patient in the practice, then you need to have a discussion with the doctor and plan a new strategy. Some options might be multiple debridement visits using adjunctive molecular iodine, decreasing the care interval, implementing a Waterpik with an antimicrobial medicament, or choosing an antibiotic strategy. This should be a case-by-case decision, but it is certain that a prophy—which is a preventive procedure—is an inappropriate treatment for patients with frank periodontitis.

Here’s wishing you all the best in deciding on courses of treatment in less-than-ideal circumstances.

References

- Herrera D, Alonso B, León R, Roldán S, Sanz M. Antimicrobial therapy in periodontitis: the use of systemic antimicrobials against the subgingival biofilm. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(Suppl 8):45-66. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01260.x

- Kornman KS, Newman MG, Moore DJ, Singer RE. The influence of supragingival plaque control on clinical and microbial outcomes following the use of antibiotics for the treatment of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1994;65(9):848-854. doi:10.1902/jop.1994.65.9.848

- American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: systemic antibiotics in periodontics. J Periodontol. 2004;75(11):1553-1565. doi:10.1902/jop.2004.75.11.1553

- Rams TE, Sautter JD, van Winkelhoff AJ. Comparative in vitro resistance of human periodontal bacterial pathogens to tinidazole and four other antibiotics. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(2):68. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9020068

Dianne Glasscoe Watterson, MBA, RDH, is a consultant, speaker, and author. She helps good practices become better through practical analysis and teleconsulting. Visit her website at wattersonspeaks.com. For consulting or speaking inquiries, contact Watterson at [email protected] or call (336) 472-3515.

About the Author

Dianne Glasscoe Watterson, MBA, RDH

DIANNE GLASSCOE WATTERSON, MBA, RDH, is a consultant, speaker, and author. She helps good practices become better through practical analysis and teleconsulting. Visit her website at wattersonspeaks.com. For consulting or speaking inquiries, contact Watterson at [email protected] or call (336) 472-3515.

Updated June 30, 2020