Proactive dental care for overall wellness: Harnessing the power of P4 medicine in oral health

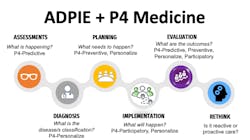

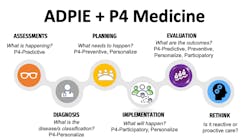

The process of care model, ADPIE (assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation) is the framework and foundation for guiding practitioners in providing effective and efficient patient care. Yet, this model can also lead to reactive care, focusing only on the symptoms of the disease and not the etiology. The same disease/condition can have many causes, and simply having a label or classification does not mean there is an understanding of why it has occurred.

A reactive approach in managing a periodontal patient may concentrate solely on meticulous plaque control. Although the etiology of periodontal disease is undisputed, the host’s inflammatory response ultimately determines the level of destruction to the periodontium, not the quantity of plaque.1 A generic reactive approach can lead to an ineffective plan and reduce positive outcomes in 20% of cases.1,2

Health-care models have evolved from disease-based to evidence-based to, now, personalized-based.3 In 2023, is the current model still adequate, or are we at a tipping point? If the objective is optimal aging for oral and overall health, then more than personalized-based care is needed. Dentistry, like medicine, has the potential to revolutionize oral health care by shifting the focus from being reactive to disease symptoms to being proactive in preventing them, and promoting aging healthy dentitions and overall well-being.

You may also be interested in ... Is a prophy without a comprehensive exam ethical—or even legal?

In 2011, biologist Leroy Hood envisioned a new health-care approach, focusing on four main pillars: predictive, preventive, personalized, and participatory care. This medical approach aims to provide patients with precise and individualized care by integrating advanced technologies and data analytics to support all the ADPIE elements rather than merely treating a disease and its symptoms. He coined the term “P4 medicine” to encapsulate these concepts.4

Predictive

Oral health diseases and conditions are multifactorial and share common risks with chronic illnesses, including genetics, lifestyle, and environment. Comprehensive dental clinical parameters are essential, but not populating the data into risk-level assessments or predictive models can misidentify patterns and focus therapy decisions on disease symptoms.4,5 A plan can be comprehensive, personalized, and predictive only if it captures the patient’s risk levels, diseases, and social determinants of health while integrating collaboration and coordination with other health and nonhealth professionals.1,2,6,7

Machine learning algorithms that manage large amounts of patient data—such as decision trees, neural networks, and supportive vector machines, which determine risk levels—are robust tools that provide predictable and effective outcomes that might not be visible through traditional practices.8 Even simply incorporating a three-tone disclosing solution can identify risk levels for decayed areas or gingival inflammation, initiating a more in-depth conversation about biofilm acidity, saliva’s buffering capacity, and nutritional counseling.

Preventive

The goal is to be proactive and prevent diseases, ultimately leading to better health outcomes and reduced health-care costs over time.9,10 The 2022 WHO report states that “oral diseases are largely preventable” and that oral health professionals’ primary focus “should be delivering evidence-based preventive care and minimally invasive interventions, supporting patients in effective self-care practices.”11

Gingivitis, defined by Trombelli et al., is a site-specific inflammatory condition12 that can elicit clinical reversible tissue changes, but the involved immune cells or trained immunity may not be reversible.13 Trained immunity refers to the enhanced response of innate immune cells to subsequent immune challenges after exposure to certain stimuli.

In gingivitis and periodontitis, chronic inflammation can lead to a state of trained immunity in the affected tissues. Studies have shown that monocytes and macrophages in the gingival tissue of individuals exhibit an altered phenotype characterized by increased expression of specific receptors and cytokines, which enhances their ability to recognize and respond to bacterial stimuli.13

Similarly, there is evidence that certain microbial products associated with periodontitis, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), can induce trained immunity in immune cells through epigenetic modifications.14,15 This suggests that exposure to oral bacteria may have long-lasting effects on the immune system, even after the infection is clinically resolved or restored to a eubiotic state. Therefore, implementing effective, antimicrobial, bioavailable therapeutic agents in self-care products to prevent gingivitis is critical, given that gingivitis is a precursor to periodontitis and perpetuates chronic inflammation.13-15

Stannous fluoride (SnF2) as a therapeutic agent must include a stabilized composition and bioavailability to effectively inhibit plaque growth, metabolism, and suppression of pathogen virulence.16 SnF2 can suppress the growth and reproduction of bacteria and inhibit the metabolic production of toxins such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), increasing host cell membrane permeability and allowing LPS and lipoteichoic acid (LTA) involved with gram-negative bacteria membranes, increasing the reactivity of toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are involved in detecting pathogens and trigger a signaling cascade.17 Crest’s proprietary SnF2 formulation can directly suppress the LPS/LTA with TLRs, reduce pathogen virulence, and support the host’s return to biocompatibility.16-19 Biesbrock et al. showed a 3.7 odds ratio in a shift to a generalized gingival health status with proprietary SnF2 formulation compared to sodium fluoride toothpaste with SnF2, achieving subgingival penetration to a depth of 4 mm.16

Klukowska et al. demonstrated that subjects brushing with bioavailable gluconate chelated SnF2 dentifrice, another propietary Crest formulation, showed a 51% greater reduction in the average number of bleeding sites versus a negative control dentifrice, and reduced plaque toxicity even at sites not yet presenting symptoms of inflammation.19

Personalized

This approach considers an individual’s unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle risks to tailor plans specific to their needs. It differs from the traditional “one-size-fits-all” approach, where treatments are often based on general population averages and reactive care.1,4

Personalized medicine has advanced with genomics and bioinformatics, the interdisciplinary field that combines biology, computer science, mathematics, and statistics to analyze and interpret biological data.1,20 The technological advancements could identify specific gene variants associated with increased risk for certain diseases or conditions by analyzing an individual’s genetic data, such as periodontal disease, oral cancers, and developmental disorders affecting the teeth and jaw.21 This field of study could allow for earlier interventions and more personalized care plans.

As technology advances, the role of epigenetics, biomarkers, and point-of-care chairside devices will likely increase in dentistry.

Participatory

This pillar of health care emphasizes active participation and engagement by patients in their own care. It recognizes that patients are experts in their own experience of illness and treatment and aims to empower them in decision-making about their health.1,4

Although comprehensive, the standard patient medical and dental history intake forms are typically closed-ended questions, which can limit the information’s quality, details, and importance. This can lead to health professionals asking several follow-up questions during the clinical appointment, which is often met with resistance from the patient.22 Self-reported forms are completed before and after the appointment and framed to give patients more time to reflect on their health and dental history, aiming for accurate, detailed information.22,23

The most common participatory oral self-care (OSC) practices and products are pivotal in achieving and maintaining oral and overall health.2,12,18 Yet, during clinical/-patient therapy appointments, the traditional approach for delivering OSC education is closer to the end or after debridement. A simple shift in OSC education delivery to the beginning of the appointment reinforces the importance of patients being active in their oral health care, supporting life-altering positive behavioral changes.

Evolving technology in oral care products, such as an electric toothbrush (EB), can support patients in achieving oral health. EB has extensive literature evidencing its ability to disrupt plaque/biofilm and reduce gingival bleeding, and an umbrella review in 2020 demonstrated its preventive benefits for periodontal diseases.24

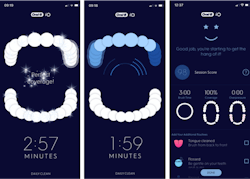

Since 1991, Oral-B oscillating-rotating (O-R) technology has supported patients’ oral health. It continues with the next generation of O-R, Oral-B iO, a complete internal and external redesign.26 The Smart Display on the handle offers immediate bimodal feedback on the pressure sensor—0.8-2.5N, indicating green for optimal pressure and effectiveness, and red resulting in a greater than 2.5N pressure. The Artificial Intelligence Technology via the Oral-B iO app (figure 1) provides real-time individual coaching using 3D teeth tracking to promote thorough brushing across all regions and surfaces, supporting patient involvement in their care.24-27

In the continuum of care, the ADPIE evaluates the plan’s outcomes; however, these evaluations are primarily clinical parameters and can perpetuate reactive approaches and focus less on patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1,4 PROs measure symptoms, quality of life, and other health aspects, essential in comprehending the patient’s experience of illness and management over time and elevating the desired oral and health benefits.28

As technology advances, there will be more examples of participatory models, given that the research clearly shows that participatory approaches in health can result in a range of benefits, including improved health outcomes, increased patient satisfaction, and reduced health-care costs.28,29

The P4 medicine approach emphasizes the use of predictive tools and technologies to identify all risks linked to oral and systemic diseases at an early stage, preventive measures to be proactive, seeks to prevent diseases through personalized therapies tailored to individual patient’s genetic and environmental characteristics, and participatory to engage patients as active partners in their health management and wellness.

By adopting these P4 concepts within the process of care model, ADPIE (figure 2) dentistry can revolutionize oral health care by shifting the focus from reactive in treating diseases to proactive in preventing them and promoting aging healthy dentition and overall well-being. The question remains: Will dentistry follow medicine and pivot from reactive to proactive care through P4 medicine?

Editor's note: This article appeared in the October 2023 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Bartold PM, Ivanovski S. P4 medicine as a model for precision periodontal care. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26:5517-5533. doi:10.1007/s00784-022-04469-y

- Kornman KS. Contemporary approaches for identifying individual risk for periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2018; 8:12-29. doi:10.1111/prd.12234

- Rhee TG, Rosenbaum L. From Hippocrates to personalized medicine: a brief history of medical practice models. J Virtual Mentor. 2013;15;(9):766-772. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.9.pmed2-1309

- Hood L. Systems biology and P4 medicine: past, present, and future. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2013;4(2):e0012.

- Weston, AD, Hood L. Systems biology, proteomics, and the future of health care: toward predictice, preventative, and personalized medicine.J Proteome Res. 3:179-196. doi:10.1021/pr0499693

- Lindhe J, Nyman S. Long-term maintenance of patients treated for advanced periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11(8):504-514. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.1984.tb00902.x

- Tonetti MS, Grenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(12):1475-1475. doi:10.1002/JPER.18-0006

- Ngiam KY, Khor IW. Big data and machine learning algorithms for health-care delivery. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(5):e262-e273. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30149-4. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jun;20(6):293.

- Harper PR, Loewen G, Welsh BY. Does preventive dental care save money? A new analysis says yes. Health Affairs. 2015;34(7):1188-1194.

- Birnbaum W, Beltran-Aguilar ED, Wen M, Brunson D. Economic evaluation of community water fluoridation: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2):264-270.

- WHO. Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Accessed Feb. 6, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484

- Trombelli L, Farina R, Silva CO, Tatakis DN. Plaque-induced gingivitis: case definition and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol. 2018;89(S1):S46-S73. doi:10.1002/JPER.17-0576

- Hajishengallis G, Li X, Mitroulis I, Chavakis T. Trained Innate Immunity and Its Implications for Mucosal Immunity and Inflammation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1197:11-26. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-28524-1_2.

- Arts RJW, Joosten LAB, Netea MG. Immunometabolic circuits in trained immunity. Sem Immunol. 2016;28(5):425-430. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2016.09.002

- Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LA, et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(8):1731-1738.

- Biesbrock A, Corby PMA, Bartizek R, et al. Assessment of treatment responses to dental flossing in twins. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1386-1391.

- He T, Zou Y, DiGennaro J, Biesbrock AR. Novel findings on anti-plaque effects of stannous fluoride. Am J Dent. 2022;35:297-307.

- Schatzle M, Löe H, Burgin W, et al. Clinical course of periodontics. I. Role of gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:887-901.

- Klukowska, Haught JC, Xie S, et al. Clinical effects of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice in reducing plaque microbial virulence I: microbiological and receptor cell findings. J Clin Dent. 2017;28(2):16- 26.

- Crofts TS, Gasparrini AJ, Dantas G. Next-generation approaches to understand and combat the antibiotic resistome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(7):422–434. doi:10.1038/nrmic ro.2017.28

- Aguado BA, Grim JC, Rosales AM, Watson-Capps JJ, Anseth KS. Engineering precision biomaterials for personalized medicine. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(424):eaam8645. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam8645

- Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. J Gen Int Med. 2010;25(7):449-454.

- Brondani MA, MacEntee MI. The concept of patient satisfaction with dentistry: a review of the literature. J Oral Rehab. 2007;34(10):759-768.

- Volman EI, Stellrecht E, Scannapieco FA. Proven primary prevention strategies for plaque-induced periodontal disease – an umbrella review. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2021;23/4:350-367.

- Thomassen TMJA, Van der Weijden FGA, Slot DE. The efficacy of powered toothbrushes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2022;20(1):3-17. doi:10.1111/idh.12563

- Adam R. Introducing the Oral-B iO electric toothbrush: next generation oscillating-rotating technology. Int Dent J. 2020;70(Suppl 1):S1-S6.

- Thurnay S, Adam R, Meyners M. A global, in-market evaluation of toothbrushing behaviour and self-assessed gingival bleeding with use of app data from an interactive electric toothbrush. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2022; 2:1-10. doi:10.3290/j.ohpd.b2572911

- Johnston BC, Patrick DL, Devji T, et al. Chapter 18: Patient-reported outcomes. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.3. Cochrane; 2022.

- Chiavellini P, Canatelli-Mallat M, Lehmann M, et al. Aging and rejuvenation - a modular epigenome model. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13(4):4734-4746. doi: 10.18632/aging.202712.

About the Author

Penny Hatzimanolakis DHP(c), BDSc. MSc. EdD(c)

Since 1994, Penny Hatzimanolakis [DHP(c), MSc., EdD (c)] practice has been with a periodontic/prosthodontic specialty team. From 2002 to now, she has facilitated learning in the graduate periodontics, undergraduate dental, and dental hygiene degree programs at the University of British Columbia, Canada. She has published and coauthored in multiple peer-reviewed journals and presented nationally and internationally. She is on several boards and a KOL for several companies. Penny volunteers in programs supporting specialized populations.