Local anesthesia options during dental hygiene care

Answers to common questions about pain control in the hygiene operatory

By Demetra D. Logothetis, RDH, MS, and Margaret J. Fehrenbach, RDH, MS

Options always exist in executing dental hygiene care, including the administration of local anesthesia. But smart dental hygiene practitioners look to evidence-based outcomes for providing successful care to their patients.

Lately, certain questions have been circulating about some of the options for local anesthesia administration that need to be considered in this bright light. This article with its open-question format endeavors to shed some understanding to these concerns by looking closely at the latest evidence surrounding local anesthesia and its administration.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Other articles of interest:

- Combating patient anxiety with clear education: Media presentations deliver the message

- Dual anesthetics preferred by most U.S. dentist anesthesiologists

- Comfortably numb: how dental anesthesia can differentiate your endodontic practice

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Lately I have noticed there is discussion about using the maximum dosages from the manufacturers with some agents rather than the lower traditional ones I am accustomed to using, and that are published in most textbooks. How does this affect my practice of dental hygiene?

Each drug has a maximum recommended dose (MRD), including local anesthetics and vasoconstrictors, which are determined by the manufacturer based on results from animal and human studies, with review and approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The maximum doses determined by the manufacturer have been reviewed by the Council on Dental Therapeutics of the American Dental Association and the United States Pharmacopeial (USP) Convention.

Maximum doses for many of the local anesthetics have been modified by experts in the field and represent the more conservative of those recommended by the Council, the USP, or the drug's manufacturer. These conservative doses have been published in most textbooks, and have been traditionally taught in many dental hygiene programs across the country.1,2 The MRD for a local anesthetic or vasoconstrictor is defined as the highest amount of an anesthetic drug that can be safely administered without complication to a patient while maintaining its efficacy.

Recently, discussions suggest eliminating the conservative dose recommended by experts in the field, and only utilizing the FDA-approved higher dosing guidelines. This has caused some confusion among dental hygiene educators, as well as dental hygiene practitioners. Questions regarding why this change is being made and how it affects the practice of dental hygiene are currently being discussed.

These dosage levels need to be considered by the dental hygienist prior to the administration of local anesthesia. Over the last 30 years, experts in the dental field have offered lower and more conservative doses that have been successfully used by dental practitioners.1 Each practitioner should determine which recommendation to follow -- the FDA guidelines or the more conservative guidelines that have traditionally been used.

There is added benefit to using the conservative guidelines because it provides additional patient safety while maintaining patient comfort. Fortunately, maximum doses are unlikely to be reached for most dental hygiene procedures. If the dental hygiene care plan involves nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) for a quadrant, the administration of one to two cartridges often suffices. There is seldom a need to administer more than four cartridges during any appointment involving dental hygiene care.3

Before proceeding with pain control, the dental hygienist must decide which dose is the specific appropriate level based on the treatment to be delivered, as well as the health status of the patient. Thus, MRDs should be adjusted to consider the patient's overall health and any mitigating medical factors that could hamper the patient's recovery.1-3 These amounts are determined based on maximum dosage for each appointment.

The dosage calculation is based on the patient's weight, and can be calculated based on milligrams per pound (mg/lb) or milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg). However, to increase patient safety during the administration of local anesthetics and vasoconstrictors, the dental hygienist should always administer the lowest clinically effective dose.

I am a student dental hygienist. How do all these different local anesthetic dosing guidelines affect my board examinations?

As a student dental hygienist, it is important to thoroughly review the candidate guide before taking any written or clinical examination. The candidate guide will inform you of the information you need to successfully pass the examination.

In the past, most board examinations have tested students on the more traditional, conservative dosages. Some board examination agencies have recently changed their dosage guidelines to reflect the FDA guidelines rather than the conservative guidelines, while other agencies have not.

Therefore, students may need to learn both sets of dosing guidelines, and use the appropriate guidelines for the examination they will be taking. If unsure which guidelines an examination will be testing you on, contact the examination agency for clarification.

Is there any real benefit to using anesthetic buffering in my practice of dental hygiene?

Dental hygienists have the unique responsibility and opportunity to alleviate pain. Fear prevents many patients from obtaining dental care, whether it is fear of dental treatment, local anesthesia, or past dental experiences. Local anesthetics cause stinging and burning upon injection, which may adversely affect fearful patients.

Anesthetic buffering is an option to help relieve stinging and burning upon injection. In the past, the benefits of anesthetic buffering were well documented in medicine.4-6 Recently, anesthetic buffering has been provided as an option for use in dentistry by using a mixing pen and cartridge connectors at chairside to provide an automated way to adjust the pH of an anesthetic cartridge immediately prior to injection.

Remember that local anesthetics used in dentistry are weak bases, and are combined with an acid to form a salt (hydrochloride salt) to render them water-soluble, which creates a stable injectable anesthetic solution. The addition of this hydrochloric acid creates undesirable qualities such as stinging and burning upon injection, relatively slow onset of action, and unreliable or no anesthesia when injected into infected tissues.2

Buffering of local anesthetics has been introduced into dentistry to counteract these undesirable qualities. Anesthetic buffering provides the practitioner a way to neutralize the anesthetic immediately before the injection in vitro (outside of the body) rather than the in vivo buffering process, which relies on the patient's physiology to buffer the anesthetic. The buffering process uses a sodium bicarbonate solution that is mixed with a cartridge of local anesthetic such as lidocaine with epinephrine. The interaction between the sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) and the hydrochloric acid (HCL) in the local anesthetic creates water (H2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2), which brings the pH of anesthetic solution closer to physiologic.2

Bringing the pH of the anesthetic toward physiologic before injection may improve patient comfort by eliminating the sting, may reduce tissue injury, may reduce anesthetic latency, and may provide more effective anesthesia in the area of infection. Thus, dental hygienists can increase patient comfort by buffering local anesthetics prior to injection.7,8

How can I be less nervous giving a posterior superior alveolar block on my patients? I do not want to give them a hematoma, so I am using infiltration instead.

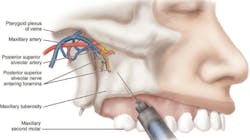

The posterior superior alveolar block (PSA) is used to achieve pulpal anesthesia in the maxillary third, second, and first molars. The target area is the posterior superior alveolar nerve as it enters the maxilla through the posterior superior alveolar foramina on the maxilla's infratemporal surface, which is at the height of the mucobuccal fold at the apex of the maxillary second molar (see Figure 1).9

Of course, for a patient with a blood-clotting disorder, local anesthetic injection techniques that pose a greater risk of positive aspiration such as the PSA block should be "avoided in favor of supraperiosteal and periodontal ligament injections, or other techniques that do not pose a threat of excessive bleeding."2 But if the patient has no overlying medical risk for bleeding, the clinician has the option of varying the depth of the needle in this area for this block to avoid complications such as a "nonesthetic" hematoma in the infratemporal fossa, a bluish-reddish extraoral swelling of hemorrhaging blood in the tissue on the affected side of the face in the infratemporal fossa that develops a few minutes after the injection, progressing over time inferiorly and anteriorly toward the lower anterior region of the cheek.

This complication can occur if the needle is advanced too far distally into the tissue during a PSA block so that the needle penetrates the pterygoid plexus of veins and the maxillary artery.9 This is a basic risk of local anesthesia; however, care must be taken to avoid this situation.

The current educational method taught in most dental professional programs, and which students are tested on in examinations, is to use a depth of needle penetration at 16 mm or less, which is three-fourths the depth of a short 25-gauge needle.1,2 In addition, clinicians recommend performing "aspiration several times within different planes before administration to reduce risk and to further reaspirate if there is any movement of the needle within the tissue."2

However, a more conservative insertion technique may be considered that is being used by clinicians with proven success so as to reduce risk of hematoma formation. This means going to less depth into the mucobuccal fold at 5-10 mm, which is only one-fourth the depth of the short needle.2 Studies are expected to be completed soon that show this conservative administration method to be successful in placing the agent near the posterior superior alveolar foramina. Remember, using a block instead of infiltration allows for more effective treatment and less discomfort for the patient.

Can I safely give a full-mouth numbing for complete calculus removal in one appointment?

First, it is important to note that gross scaling where large-sized supragingival calculus is removed at the initial appointment is no longer recommended. Instead, two types of periodontal therapy can be considered for patient care during Phase 1 periodontal therapy (nonsurgical phase). Full-mouth debridement is a newer procedure where calculus is removed in a single appointment or more commonly now in two appointments within a 24-hour period, sometimes with the aggressive use of antimicrobial agents for full-mouth disinfection (FMD).10

The more traditional approach is nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT). Studies have shown that "the modest differences in clinical parameters in comparing healing after one session or multiple sessions were not clinically significant."11 In addition, microbial parameters were not significantly different after eight months, regardless of treatment.12

Until evidence indicates otherwise, the sequence and duration of appointments for periodontal therapy should be determined by the clinician based on amount of disease present and the patient's systemic health as well as comfort, and not patient preference or insurance needs. However, staged therapy permits "the advantage of evaluating and reinforcing oral hygiene care," which is key to the effectiveness of Phase 1.3

So whether performing FMD or NSPT, the dental hygienist should carefully determine "the extent of periodontal involvement, and how much of the treatment can be realistically accomplished in one visit.2 Local anesthesia use is based on many factors (not listed in importance) such as limited pocket access and topography, tissue tone, root anatomy, hemorrhage risk, as well as the patient's pain threshold and sensitivity.3 Even when using ultrasonics, local anesthesia should be given prior to use with high power to ensure that the patient is comfortable.13

For dental hygienists who are prohibited by state law from administering local anesthesia who may be tempted to start scaling heavy calculus with thin tips on low power to increase patient comfort, experts have noted a burning of heavy calculus into smooth veneers, visible only with a dental endoscope or during open-flap surgery but still able to serve as an "ideal breeding ground for biofilm."14 Thus, local anesthesia should only be administered in the areas of treatment that can be completed in one visit. Overestimating the treatment and administering more anesthesia than necessary should be avoided.2

More importantly, any performance of successful periodontal debridement, whether FMD or NSPT, requires the complete removal of any clinically detectable calculus. Calculus removal is critical to the success of periodontal therapy because calculus retains dental biofilm. Also, there will probably never be one simple standard for assessing the clinical endpoint because the patient's systemic health, immune response, and self-care practices influence healing. Sound professional judgment must be practiced "to determine endpoints of periodontal therapy. Intentionally leaving detectable calculus, therefore, constitutes unethical or substandard care."3

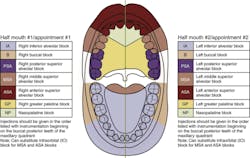

However, the dental hygienist should avoid administering local anesthetics to both the mandibular right and left quadrants during a single treatment to prevent the inability of the patient to control his or her mandible; thus the use of quadrant or half-mouth procedures is usually recommended (see Figure 2). Clinicians report that patients have a hard time swallowing, and replacement of any removable prosthetics or eating soon after can cause gagging. Also, when designing the dental hygiene care plan, the dental hygienist must consider the amount of anesthetic needed to complete the procedure so that they are always staying within the patient's MRD (see earlier question on dosage).15 In addition, administering bilateral inferior alveolar nerve blocks also increases the possibility of the patient causing self-mutilation of their soft tissue.9

There is some discussion about using the AMSA on patients for periodontal therapy. Should I consider it?

The anterior middle superior alveolar (AMSA) block can be used for anesthesia of the periodontium and gingival tissue covering a large area that is normally innervated by the anterior superior alveolar (ASA), middle superior alveolar (MSA), greater palatine (GP), and nasopalatine (NP) blocks in the maxillary arch (see Figure 3). Thus, with a single-site palatal injection, one can anesthetize multiple teeth (from the maxillary second premolar through the maxillary central incisor) and associated periodontium without causing the usual collateral anesthesia to the soft tissue of the patient's upper lip and face. That is why it is commonly used when performing cosmetic dentistry procedures, because after the procedures are completed, the clinician can immediately and accurately assess the patient's smile line.

It is also important to remember that the posterior superior alveolar block (PSA) must still be administered to allow for pulpal anesthesia in the maxillary third, second, and first molars.2

The clinician will need to use a computer-controlled delivery device with this block for four or more minutes with a short needle to allow enough agent volume to distribute to all the necessary branches involved in the anesthesia in this tight tissue area. Said diffusion will take about as long. This was the standard method used in the original research of the block because the device regulates the pressure and volume ratio of solution delivered, which is not readily attained with a manual syringe.16,17 In fact, most past studies concerning this block have been done with these devices since the block was discovered while developing the device.

Thus, it is not true that only a minimal volume of local anesthetic is necessary to provide pulpal anesthesia from the maxillary central incisor to the maxillary second premolar on the side of the injection, but instead one must deposit "a sufficient volume of local anesthetic (that) allows it to diffuse through nutrient canals and porous cortical bone on the palate..."1 Further, any related discussion of what some have conjured up as a "subneural" dental plexus deep to the major branches of the maxillary nerve that is supposed to respond to anesthesia is not truly present according to master anatomists.9 Instead, the major branches of the maxillary nerve act together as dental plexus and respond as such to anesthesia in the area.

Practiced clinicians know already how hard it is to place even the necessary smaller amounts of agent during the GP and NP blocks using a manual syringe. Still, some clinicians think they can use a manual syringe with the AMSA, but it would mean reinjecting the agent multiple times and possibly causing overblanching the tissue, leading to postoperative tissue ischemia and sloughing. A recent study using a manual syringe demonstrates the difficulty of administering enough volume.18 The added cost of this anesthetic delivery system is one potential drawback of the AMSA block.

However, even after depositing a large enough amount of agent using the computer-controlled delivery device, studies show that due to the extensive anatomy involved, the block may be variable in depth and duration of anesthesia, which may compromise its use for nonsurgical periodontal therapy. NSPT usually requires full depth (pulpal of quadrant) and long duration of anesthesia (more than 60 minutes) to complete the treatment.18,19

Some past articles on this block are overly optimistic about the time of administration (only two minutes) and diffusion (only two minutes) as well as length of duration (as long as 90 minutes), which does not serve the practicing clinician well. Attempts to speed up the AMSA block may lead to increased patient discomfort at the injection site.20

Again, recent studies showed a "duration of pulpal anesthesia was gradually declining during the 60 minutes; we cannot confirm the clinical impression of the authors that there is duration of pulpal anesthesia for 60 minutes."18

It is important to note that the initial study using this injection with the computer-controlled delivery device for scaling and root planing was small (20 subjects, split-mouth design) and relied on subjective responses from patients on depth of anesthesia using "visual analog scales and verbal ratings."21 One of these studies using an electric pulp tester showed only "a 66% anesthetic success in the second premolar, 40% in the first pre-molar, 0% in the canine, 23.3% in the lateral incisor, and 16.7% in the central incisor." Another similar study of the computer-controlled delivery device reported successful pulpal anesthesia ranged "from 35% to 58%, and for the manual syringe even lower rates from 20% to 42%."18,19 It is hard to argue for the AMSA block with those lowly numbers.

Other studies noted cases of short-lived anesthesia in the maxillary central incisor region.20,22 Thus, the nature of the palate does not always allow penetration from the palatal to the facial in order to provide pulpal anesthesia, especially to the faraway maxillary central incisor. Possibly additional facial infiltration can be performed to ensure complete coverage of the quadrant, or even reinjection with another AMSA block when anesthesia is inadequate, but that reduces the positive impact of fewer injections that the AMSA promises.

In addition, these past articles made no mention of the less-than-stellar hemostatic control of the quadrant's overall gingival tissue as later studies confirmed. These studies only demonstrated hemostatic control with the palatal tissue, making it an excellent block for graft harvesting, and with no vasoconstrictor affecting the facial gingiva, outstanding blood supply is maintained for nourishment after the placement of the connective tissue graft.18,20

Instead, reliance on the traditional blocks for the maxillary arch may allow the dental hygienist to treatment plan instrumentation in either quadrants or within sextants with more confidence of pain and hemostatic control.2

I heard about a new technique for giving the incisive block on my patients. How does it work?

The incisive block anesthetizes the pulp and periodontium of the mandibular teeth anterior to the mental foramen, usually the mandibular premolars and anteriors, as well as the facial gingiva. One indication for the use of this block is for NSPT on the mandibular anterior sextant.

However, the incisive block does not provide lingual soft-tissue anesthesia of the anesthetized teeth; an additional supraperiosteal injection may be indicated for localized lingual soft-tissue anesthesia and/or hemostatic control. Since bilateral inferior alveolar (IA) blocks are usually not recommended and IA blocks can even fail, the bilateral use of the incisive block lingual supraperiosteal injection is a ready replacement in many situations (see earlier discussion).2

The target area for the incisive block is anterior to where the mental nerve enters the mental foramen to merge with the incisive nerve and form the inferior alveolar nerve (see Figure 4).9 There are many ways to approach this target area, but one of the new ways is to use a horizontal approach.

The older injection protocol recommends that the clinician sit behind the patient and use a vertical approach with the syringe into the target tissue. Visibility was “poor for the clinician to see the target tissue as well as the large window on the syringe to check for negative aspiration. More importantly, the patient was often alarmed at seeing the syringe with needle coming down between their eyes.”24

With the newly recommended horizontal approach, the clinician sits more along the side of the patient, providing better visibility and obstructing the patient’s line of sight of the advancing syringe and needle (see Figure 5). In this position, the needle tip with its bevel toward the bone can gently slide past the periosteum, and there is no possibility of injury by scraping the periosteum or going through the lower lip. The injection is “relatively painless, and the landmarks are reliable and consistent.”9

Before administration, retract the patient’s lower lip outward, using gauze, to pull the tissue taut. The injection site itself is anterior to the depression created by the mental foramen in the depth of the mucobuccal fold found earlier by palpation. Using a 27-gauge short needle, direct the syringe barrel from the anterior portion of the mouth to the posterior in a horizontal manner, while resting on the lower lip.

This will keep the needle syringe out of the patient’s view. The needle is advanced without contacting the bony surface of the mandible, with the depth of penetration at 5 to 6 mm. The injection is slowly administered after negative aspiration within two planes.23

Placing the patient in an upright or semiupright position while massaging the anesthetic agent has been shown to promote further diffusion of the solution into the region via gravity.2

So, when considering your next periodontal maintenance case or mandibular anterior sextant patient, or when faced with the failure of the IA block to fully anesthetize the mandibular anteriors, try utilizing the incisive block using the horizontal approach.

As we look over these questions concerning options in local anesthetic administration during dental hygiene care and apply evidence-based answers, the background noise surrounding these concerns lessens. Smart dental hygiene practitioners now can see how to obtain successful outcomes for their patients during local anesthesia administration.

Demetra Daskalos Logothetis, RDH, MS, is emeritus professor and program director at the University of New Mexico Department of Dental Medicine, and currently visiting professor and graduate program director in the university's Division of Dental Hygiene. Demetra has been a professor at the University of New Mexico for 28 years, and served as the dental hygiene program director for 16 years. She has been teaching local anesthesia for 19 years, and is the author of "Local anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist," (Elsevier, 2012) that received honorable mention at the 2013 PROSE awards. This textbook is exclusively related to local anesthesia for the practice of dental hygiene.

Margaret J. Fehrenbach, RDH, MS, is an oral biologist and dental hygiene educational consultant. Margaret recently received the AC Fones Award from ADHA (2013) for her work in promoting local anesthesia for dental hygienists, such as "Local anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist" (Elsevier, 2012) as well as the ADHA Award of Excellence (2009) for her textbook contributions. She is the primary author of the "Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck" (Elsevier, ed 4, 2012) and "Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy" (Elsevier, ed 4, 2015) as well as a contributor to "Oral Pathology for Dental Hygienists" (Elsevier, ed 6, 2104) and editor of the "Dental Anatomy Coloring Book" (Elsevier, ed 2, 2013). Margaret has presented at ADEA, ADHA, and ADA Annual Sessions as well as Under One Roof for RDH Magazine. She is now involved in webinars and radio broadcasts as well as social media outlets. She can be contacted through her webpage at www.dhed.net.

References

1. Malamed SF. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 6 ed, Mosby, 2012.

2. Logothetis. Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist. Elsevier, 2012.

3. Darby, Walsh. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 3 ed, Saunders, 2010.

4. Bowles, Frysh, Emmons. Clinical evaluation of buffered local anesthetic. General Dentistry. 43(2), 182, 1995.

5. Stewart, Cole, Klein. Neutralized lidocaine with epinephrine for local anesthesia. Journal of Dermatological Surgery in Oncology. 15(10), 108, 1989).

6. Malamed SF, Tavana S, Falkel M. Faster onset and more comfortable injection with alkalinized 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2013, Feb: 34, Spec No 1: 10-20.

7. Logothetis D. Anesthetic buffering: New advances for use in dentistry. RDH, January 2013.

8. Logothetis D. Local anesthetic agents: A review of the current options for dental hygienists. Journal of the California Dental Hygienists' Association, Summer 2011.

9. Fehrenbach, Herring. Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, 4 ed, Saunders, 2012.

10. Perry, et al. Periodontology for the Dental Hygienist, 4 ed, Saunders, 2014.

11. Newman, et al. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology, 11 ed, Saunders, 2012.

12. Rethman J. Is full-mouth disinfection right for your practice? Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2008.

13. Pattison A. Using thin ultrasonic tips on high power. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2009.

14. Pattison A. Manage your patients' pain. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2011.

15. Fehrenbach M. Pain control for dental hygienists: Current concepts in local anesthesia are reviewed. RDH, February 2005.

16. Bath-Balogh, Fehrenbach. Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy. 3rd ed, Saunders, 2011.

17. Loomer, Perry. Computer-controlled delivery versus syringe delivery of local anesthetic injections for therapeutic scaling and root planing. Journal of the American Dental Association. 135(3):358-65, 2004.

18. Velasco, Reinaldo. Anterior and middle superior alveolar nerve block for anesthesia of maxillary teeth using conventional syringe. Dental Research Journal. 9(5): 535–540, 2012.

19. Lee, et al. Anesthetic efficacy of the anterior middle superior alveolar (AMSA) injection. Anesthesia Progress. 51(3):80-9, 2004.

20. Alam, et al. AMSA (Anterior Middle Superior Alveolar) injection: A boon to maxillary periodontal surgery. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 5:675-678, 2011.

21. Perry, Loomer. Maximizing pain control: The AMSA injection can provide anesthesia with fewer injections and less pain. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 1: 28-33, 2003.

22. Corbett, et al. A comparison of the anterior middle superior alveolar nerve block and infraorbital nerve block for anesthesia of maxillary anterior teeth. Journal of the American Dental Association. 141(12):1442-8, 2010.

23. Fehrenbach. The horizontal incisive block underutilized but ultimately useful. Journal of the California Dental Hygienists' Association, Summer 2011.

Past RDH Issues