Does leishmaniasis go undiagnosed? Lesions resulting from sandfly infection require prompt response

By Nancy W. Burkhart, BSDH, EdD

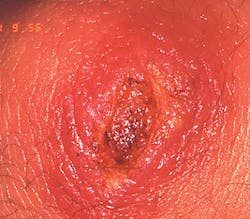

Your patient today is a 16-year-old male who just spent his summer on a high school project in South America. He was working with a group who assisted disadvantaged individuals, helping to rebuild or refurbish homes. After returning home at the end of the summer, he noticed an area on his upper lip that continued to grow and became ulcerated.

He is a patient of record in your office, and is scheduled for a routine yearly visit. He calls this area on his lip to your attention and asks your opinion about ways he can get it to heal. He tells you that the appearance is really causing him anxiety. Although you are not certain about the etiology, what would you want to ask him and what would you place on your differential list of a possible etiology (see Figure 1)?

Etiology: The lesion is called leishmaniasis (and also kala azar), and it is considered a parasitic disease. Leishmaniasis is found in the tropics and in the southern United States in areas such as Texas and Oklahoma. Leishmaniasis is caused by the bite of the female sandfly and transferred to the tissue of the host. The parasite multiplies within the cytoplasm of host cells. The protozoan parasite of the genus leishmania is the cause of the disease.

Method of transmission: Leishmaniasis is transmitted by the female sandfly.

Epidemiology: Skin diseases and sometimes oral lesions are the most commonly reported complaint by world travelers. With increases in travel reported worldwide and many military serving in these areas, dental offices can expect that they will see more skin/oral lesions related to leishmaniasis.

This may involve very unusual presentations of skin lesions. Many of the lesions involve the face, neck, and ear area that are most visible to dentists and hygienists. Leishmaniasis is typed into two forms titled "old world" and "new world," depending upon the region of the world. It is estimated that approximately 12 million forms of the leishmaniasis are found globally; 1.5 million are cutaneous. Mortality is estimated at 20,000 to 30,000 annually worldwide.

Figure 1: Courtesy of Dr. Doron J. Aframian from "General and Oral Pathology for The Dental Hygienist" by DeLong and Burkhart. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Baltimore. 2013.

The main parts of the globe where more than 90% of leishmaniasis is found are in areas such as Brazil, Peru, southern Europe, Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Central and South America. Leishmaniasis accounts for up to 5% to 10% of all travel-related disease with increases seen recently (Vasievich, et al. 2016). Overall, the CDC reports that leishmaniasis has been found in more than 90 countries.

Studies by Khosrvani et al. (2016) reported statistical findings of 1,908 patients with the most frequent age group over 20 years of age. Hand ulcers were the most prevalent part of the body with 43.24%. The visceral organs can be involved, mainly the liver, spleen, and bone marrow with the visceral type of leishmaniasis.

Pathogenesis: Interestingly enough, if the female sandfly bites an infected human host, the parasites are transferred to the gut of the fly, and the fly can infect another host. The cycle is continued. The fly is smaller than a mosquito and does not make a sound. The bite is painless. There is a one- to two-month incubation period.

Extraoral characteristics: The cutaneous lesions usually present as a solitary, circumscribed erythematous papule at the entry site of the sandfly bite. The papule continues to large, is indurated, and continues to enlarge with nodules and eventually ulceration.

Perioral and intraoral characteristics: There are forms of leishmaniasis that can occur one to two years after the primary cutaneous occurrence. That involve erythema, edema, and changes in the mucosa with drainage. The mucous membranes can be affected and destruction of tissue is possible if the etiology is not recognized. The progression from cutaneous to mucocutaneous rates are from 1% to 10%.

Distinguishing characteristics: Long-term, nonhealing cutaneous lesions that persist over time, fever, weight loss, pallor, and lymphadenopathy.

Significant microscopic features: Skin biopsies note histocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells. Polymerase chain reaction will confirm the diagnosis. Multiple tests may be involved in a definitive diagnosis.

Dental implications: Recognition of cutaneous lesions on visible parts of the body is important so that early treatment for the disease can begin. Any nonhealing lesion should be evaluated, and unknown causes referred to a dermatologist. A key finding would be the fact that there has been travel to areas where the sandfly bite is rampant. Since the bite is painless and goes unnoticed, leishmaniasis would not be at the top of the list of a possible etiology.

Differential diagnosis: Viral infections, bacterial infections, fungal infections, and always malignancy would be considerations. Some other lip lesions that may have a similar clinical appearance at certain stages are keratoacanthoma and basal cell carcinoma.

Treatment: Treatment involves various antimonials. The infecting species will determine treatment. Cure rates average from 52% to 95%. Skin lesions will sometimes heal on their own, but it may take months to years. High trauma areas such as the lips may be more inflamed and take longer to heal (CDC, 2016).

An Oral Medicine Perspective

After questioning the patient, if leishmaniasis is suspected because of travel to other countries or location in the United States, the patient should be referred to their physician and then to an infectious disease specialist. Leishmaniasis is increasing in certain countries at alarming rates. In countries where we have not seen this disease very often, the diagnosis may be delayed because it is unrecognized.

Treatment needs to begin as soon as possible. Many service personnel have been stationed in areas where this may be a problem; therefore, returning military may be a susceptible group. Multiple types of medications may be needed, and treatment from someone who is knowledgeable in these types of worldwide disease states needs to be involved.

Although the dental community cannot treat leishmaniasis, we do have a duty to recognize those entities that are beyond our scope of practice and secure needed treatment for our patients without delay. Since we are involved with the facial/oral structures and our prime focus is on this particular area of the body, we may be the first to recognize this disease state.

As always, continue to ask good questions and always listen to the answers. RDH

References:

1. DeLong L, Burkhart NW. General and Oral Pathology for The Dental Hygienist. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Baltimore 2013.

2. Khosrvani M, Moemenbellah-Fard MD, Sharafi M, Rafat-Panah A. Epidemiologic profile of oriental sore caused by Leishmania parasites in a new endemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniansis, southern Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2016 Sep;40(3):1077-81.

3. Prajapati R, Kumar A, Sharma P, Singla V, Bansal N, Dhawan S, Arora A. A rare presentation of Leishmaniasis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016 June; 6(2): 146-8.

4. Vasievich MP, Villarreal JD, Tomecki KJ. Got the travel bug? A review of common infections, infestations, bites, and stings among returning travelers. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016; DOI 10.1007/s40257-016-0203-7.

NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics/stomatology, Baylor College of Dentistry and the Texas A & M Health Science Center, Dallas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (http://bcdwp.web.tamhsc.edu/iolpdallas/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. She was awarded a 2016 Academic Affiliate Fellowship (AAF). She was a 2006 Crest/ADHA award winner. She is a 2012 Mentor of Distinction through Philips Oral Healthcare and PennWell Corp. She can be contacted at [email protected].