Light up your operatory and career with lasers

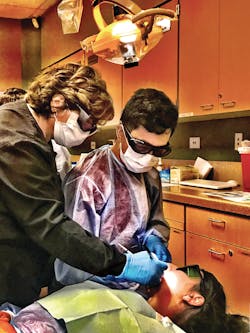

Editor’s note: Some of the images in this article were taken prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and may not reflect current infection control recommendations.

Why diode lasers? Why now? As oral health-care providers, today’s dental hygienists are looking for ways to minimize bacterial and viral loads for our patients’ health and our own safety. Diodes are the most common and economical lasers used in hygiene. They can serve as a first line of defense in our preventive approach to patient care.

Laser bacterial reduction (LBR), along with preprocedural rinsing, will allow the clinician to confidently decontaminate and reduce cross-contamination in the mouth prior to other procedures.1

Dental hygienists primarily use lasers for decontamination, disinfection, and biostimulation through the absorption of light energy into the periodontal tissues.2,3,5,11 The healing benefits of lasers through the reduction of inflammation, disinfection, and the elimination of bleeding speak to the true value of laser implementation into the evolving hygiene model of care.2 We need to rethink all of the biological and physiological processes involved and implement new treatment protocols and strategies,1,4 thereby changing the way we think about how we practice and the services we provide.

Now, more than ever, patients know that bacteria and viruses are bad news. Patients will have more confidence in dental offices where action is taken toward improved models of care, technology, and service that protects the public’s health. These patients will remain dedicated to the practice and are more likely to move forward with treatment. They will refer their family and friends, earning you the respect as their trusted oral health-care provider.

Light up your career

“I encourage every RDH to seek advanced continuing education and training in order to evolve with today’s modern technology and science. RDHs can deliver comprehensive care for their patients if they find the working environment where they feel safe, trusted, and respected. Finding the right practice fit is essential to long-term career satisfaction.”—Dangler

Like most of you, I love dental hygiene and am always looking for ways to advance my personal development. This career has provided me with lifelong relationships and a tribe of caring, compassionate professionals who possess grit. I have been fortunate to have worn many hats in our field as clinician, educator, speaker, corporate manager, consultant, and dental salesperson. I believe all hygienists can reignite their passion in the op if they are set up and supported to practice the way they were trained as oral health-care providers.

Today’s comprehensive care model

A thorough medical and dental health questionnaire connecting systemic indices; vitals; a thorough intraoral and extraoral exam with advanced technology screening for oral abnormalities; an airway and/or breathing disorder assessment; a thorough periodontal, malocclusion, and ortho assessment; risk assessments; radiographs; photos and scanning … I know what you’re thinking: “Wow! All this before picking up a scaler! Who has time for that?”

Diode lasers were one of the first technologies I learned about after hygiene school. Lasers have provided me with additional skills to achieve enhanced healing and treatment modalities for my patients. This technology adds value for patients, and I am rewarded with personal satisfaction. In my experience, patients are healthier and more committed to keeping their supportive maintenance appointments, and our offices are more productive, with yearly growth in revenue, increased referrals, and patient retention.

“With continuing education, training, and advanced technology available to provide patients with the highest standard of care, I see my colleagues reignite their passion and love for what they do every day as oral health-care providers. My why is fulfilled when I know patients are receiving great care, and my colleagues have the ability to deliver their best work and embrace their role as a valuable member of the team, practice, and the business. Dental hygiene is so much more than just cleaning teeth.” —Dangler

Now let’s talk diode lasers

The term LASER is an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. Simply stated, a laser is a device that produces and amplifies light.5–7 It is the wavelength of this light—where it sits on the electromagnetic spectrum of light—that determines the proper use of the laser energy beam.5

Different forms of laser energy affect tissues in different and specific ways. The diode wavelength used in hygiene disinfection and debridement—typically 810 nanometers (nm) to 980 nm—is readily attracted and absorbed by tissue pigments, hemoglobin, and melanin.5–7 This unique absorption of light energy is what makes the laser ideally suited to disinfect, eliminate periodontal inflammation, destroy infective biofilms, stop the bleeding coming from existing periodontal wounds, and initiate biostimulation.7

When laser energy is absorbed by soft tissue, the result is a localized conversion to heat, which results in a nonionizing photothermal reaction, essentially converting light into heat within biologically acceptable thermal limits.6 This thermal reaction affects the bioburden.

The dental hygienist “shines the light” from the laser into the sulcular space to create a thermal event that does not alter tissue, but simply decontaminates and reduces bacteria in the pockets. Hygienists are able to incorporate lasers in treatment, because unlike the surgical lasers used by dentists, the laser energy settings hygienists use do not vaporize or ablate the tissue.7

What can a laser do?

Based on the energy settings applied, diode lasers are used for bacterial reduction (LBR) and sulcular debridement (laser-assisted periodontal therapy; LAPT) to disinfect and initiate the body’s host immunological response for healing.2,3,8,9 In addition to its bactericidal effects in preprocedural disinfection, the laser is also an ideal instrument when specifically used during periodontal therapy (LAPT) due to its ability to destroy bacteria, reduce inflammation, and heal the periodontal wound when used adjunctively during periodontal debridement (i.e., scaling and root planing).1,4,9,10 This bacterial reduction is critical to the reduction of destructive chemical mediators, which allows the body to heal from the destruction caused by biofilm-induced gingivitis, periodontitis, and implantitis.

“The diode laser is a tremendous asset for the dental hygienist to jump-start change in the eyes of patients. Tell the patient: ‘Since we saw you last there have been a lot of changes in dentistry. Science has given us new tools that safely and effectively allow us to help disinfect the gum tissues at the beginning of your appointment by lowering bacteria right from the start with the use of a laser.'"—Press

It is the dynamics of wound response during LAPT that takes periodontal health to levels of healing beyond traditional treatment applications.2,3 The laser kick-starts the immune system’s ability to heal while destroying bacteria that is present.2 Photons (light energy) energize the body to heal through stimulation of the fibroblasts and mitochondria, which have been negatively affected due to the presence of disease. These physiologic changes occur through laser biostimulation to initiate the body’s own healing process. Laser implementation is utilized in periodontal therapy as an adjunct to standard SRP, with the expectation of a clinical change in the microflora and gingival wound healing.2,3,5,8,9,11

Effective communication

Effective patient communication is always critical. It is important that patients understand how an infection in the mouth can affect all other parts of the body, but that the infection is easily treatable. By using language such as “laser-assisted periodontal therapy that includes laser debridement and bacterial disinfection” rather than “scaling and root planing,” the hygienist is able to bring new treatment awareness and raise the patient’s interest and attention to the changes in treatment. Lasers are safe to use and provide improved and more rapid wound healing—making our patients feel more comfortable after treatment.

Personal experience as a laser RDH

Luckily, my doctor invested in an amazing mentor and trainer who came to our office to provide over-the-shoulder training and coaching to ensure our use of the laser was correct for each patient. She not only enriched my clinical laser skills, but also taught me communication strategies that gave me confidence in my conversations with patients.

“This new role being assumed by hygienists benefits both practice and patient by making periodontal care more effective and by establishing a higher level of treatment acceptance and production.” —Press

Her experience and coaching were invaluable in my laser education journey and the reason I have a strong affinity for laser training beyond standard proficiency courses. After seeing results and hearing positive feedback from patients, I quickly became an evidence-based believer and laser advocate.

“Hands-on training can make all the difference in your success and confidence when implementing lasers into the practice. Having a mentor and/or experienced coach is priceless.”—Dangler

Demystifying laser education myths

There is confusion regarding laser use by dental hygienists. Licensed dental professionals seek continuing education in all areas of direct patient care as a professional standard. Developing new skill sets requires practice, educational interest, and the desire to expand our knowledge.

It is important to bear in mind that the laser is a device—cleared by the FDA—to perform laser bacterial reduction sulcular debridement (curettage) in dental hygiene and soft-tissue surgical applications by the dentist. Few states have a formal rule regarding hygiene laser education requirements. Typically, we hear about suggested guidelines for laser training, which are recommendations and should not be viewed as a required state rule. The authority to define a rule lies with each state’s dental board. Therefore, dental hygienists should look to their general scope of practice policies when determining duties they are asked to perform.

The real question we should be asking is not what instruments are we permitted to use, but what procedures can we perform and for what purposes. Twenty states have specific formal rules supporting laser use by hygienists; board-certificed CE is required. Eighteen states have no such formal rules. In this case, our profession assumes we will seek education to attain confidence and competency. Twelve states have formal rules prohibiting any use of a laser by hygienists.

“The changing face of periodontics and the role of the hygienist in treating patients to a new level of health and wellness should be viewed as inspiration to becoming more knowledgeable and skilled in incorporating a laser.” —Press

Continuing education programs on the science of laser physics, clinical application, and practice implementation are available. These programs, which follow accepted curriculum guidelines for dental laser education, are available through qualified consultants and clinical trainers, manufacturers, and membership organizations. Attendees receive a certificate for 8 to 12 continuing education credit hours. Dental hygienists should commit to acquiring knowledge of the principles of laser use and the simulation skills to clinically deliver treatment.

Return on investment

The extensive utilization of lasers in medicine, from dermatology to neurology, has set the stage for patient awareness and interest in laser-assisted dentistry. In recent years, diode lasers have become more portable and affordable, which has dramatically increased their presence in the general dental practice for therapeutic and efficient surgical applications. There are even lasers that are designed specifically for use by dental hygienists for LBR and LAPT.

This increased awareness of noninvasive dental applications with the 810–980 nm diode laser—such as for treatment of implantitis, herpetic lesions, aphthous ulcers, and doctor surgical procedures (e.g., gingivectomy, fibroma removal, frenectomy, and other soft tissue applications)—allows hygienists to discuss additional same-day procedures during routine preventive appointments.5–7

“We cannot help but look to the science that is currently being presented and feel compelled to further investigate the possibilities available to safely treat our patients to health and wellness.” —Press

Hygienists are now able to establish an educational dialogue and trust with patients that can be extended into other revenue-bearing procedures, immediately increasing treatment acceptance, which translates into economic growth in the doctor’s schedule as well. Figure 1 demonstrates the kinds of returns practices see on this investment.

Conclusion

The range of appropriate use for lasers will continue to expand, requiring clinicians to examine how they deliver safe and effective treatments with minimal inconvenience and no procedural or postoperative patient discomfort.2

Incorporation of dental lasers into the practice will increase quality of treatment, offering clinical and patient benefits with an added dimension to the value of the dental hygiene profession in the practice of modern dentistry.

Authors’ note: This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Terry Myers (May 4, 2020). A true visionary, Dr. Myers’ pioneering contribution and dedicated belief in laser dentistry for more than 30 years paved the way for lasers in our practices today. We owe him a heartfelt debt of gratitude for his inspiration and mentorship as we continue his legacy by providing our patients with the incredible benefit of laser-assisted hygiene.

References

- Scannapieco FA. Periodontal inflammation: from gingivitis to systemic disease? Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2004;25(7Suppl):16-25.

- Ciancio SG, Kazmierczak M, Zambon JJ, Baumgartner S, Bessinger MA, Ho A. Clinical effects of diode laser treatment on wound healing. J Dent Res. (Spec Iss A):2183.

- Haraszthy VI, Zambon MM, Ciancio SG, Zambon JJ. Microbiological effects of 810 nm diode laser treatment of periodontal pockets. J Dent Res. (Spec Iss A):1163.

- Mariotti A. A primer on inflammation. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2004;25(7 Suppl 1):7‐15.

- Myers TD. Lasers in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122(1):46‐50. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1991.0018

- Coluzzi DJ, Convissar RA. Lasers in clinical dentistry. Dent Clin North Am. 2004;48(4):xi‐xii. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2004.06.003

- Coluzzi DJ. Fundamentals of dental lasers: science and instruments. Dent Clin North Am. 2004;48(4):751‐v. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2004.05.003

- Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, et al. Treatment of periodontal pockets with a diode laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22(5):302‐311. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1998)22:5<302::aid-lsm7>3.0.co;2-t

- Moritz A, Gutknecht N, Doertbudak O, et al. Bacterial reduction in periodontal pockets through irradiation with a diode laser: a pilot study. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1997;15(1):33‐37. doi:10.1089/clm.1997.15.33

- Fontana CR, Kurachi C, Mendonça CR, Bagnato VS. Microbial reduction in periodontal pockets under exposition of a medium power diode laser: an experimental study in rats. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;35(4):263‐268. doi:10.1002/lsm.20039

- Food and Drug Administration 510(k) Clearance of the Biolase Epic 980. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf19/K193486.pdf

Pfitzner A, Sigusch BW, Albrecht V, Glockmann E. Killing of periodontopathogenic bacteria by photodynamic therapy. J Periodontol. 2004;75(10):1343‐1349. doi:10.1902/jop.2004.75.10.1343

Valerie Dangler, BSDH, RDH, is a registered dental hygienist in Arizona, Utah, and Georgia. She received her laser certification at the Las Vegas Institute of Advanced Dental Studies and is board certified to provide dental local anesthesia and nitrous oxide. She serves as a faculty speaker and educator for Align Technology and Biolase, and provides training and development for dental team members across the country. She can be reached at [email protected].

Janet Press, RDH, FALD, is a dental hygiene graduate of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and has been in general and periodontal specialty practices since 1975. Press holds a fellowship in laser dentistry and received soft-tissue laser certification training in 1995. Internationally recognized in dental hygiene laser education, she has provided laser training in the academic environment as well as the private sector for more than 20 years. Press was named “Distinguished Dental Professional” by Dentsply International and is the owner of 21st Century Dentistry, an approved CE provider for laser certification offering training throughout the United States. Contact her at janetpress.com.

About the Author

Valerie Dangler, BSDH, RDH

Valerie Dangler, BSDH, RDH, is a registered dental hygienist in Arizona, Utah, and Georgia. She received her laser certification at the Las Vegas Institute of Advanced Dental Studies and is board certified to provide dental local anesthesia and nitrous oxide. She serves as a faculty speaker and educator for Align Technology and Biolase, and provides training and development for dental team members across the country. She can be reached at [email protected].

Janet Press, RDH, FALD

Janet Press, RDH, FALD, is a dental hygiene graduate of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and has been in general and periodontal specialty practices since 1975. Press holds a fellowship in laser dentistry and received soft-tissue laser certification training in 1995. Internationally recognized in dental hygiene laser education, she has provided laser training in the academic environment as well as the private sector for more than 20 years. Press was named “Distinguished Dental Professional” by Dentsply International and is the owner of 21st Century Dentistry, an approved CE provider for laser certification offering training throughout the United States. Contact her at janetpress.com.