Full-mouth series x-rays vs. cone-beam computed tomography: What dental hygienists need to know

Radiographic imaging has been used in dentistry since 1895.1 Over the years, dental radiographs have evolved in terms of clarity and the equipment used to construct them.1 Currently, it’s estimated that more than half of dental offices in the US operate their practices with digital radiographic software and equipment.2

Digital radiography has many benefits, such as instant development, decreased radiation exposure to patients, fewer overhead expenditures to the practice, and overall ease and patient comfort.1 As dental offices add more digital dental equipment, hygienists need to understand the importance of two of the more commonly imaged digital radiographs: the full-mouth series (FMS) and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT).

Full-mouth series

An FMS is a set of 18 to 20 individualized radiographs that capture the details of a patient’s oral cavity.1 It’s made up of bitewing radiographs, anterior and posterior periapicals that help detect caries, oral pathology, and periodontal disease.1 A digital FMS can be taken with a wireless or wired digital radiographic sensor, a mounted or handheld x-ray unit, and a computer imaging software system.1 Bitewing and periapical radiographs are two-dimensional images of three-dimensional objects, so discrepancies about certain radiographic artifacts in the images may be subjective.

All patients should have an FMS exposed about every three to seven years, depending on their oral disease status.1,3 An FMS guides an RDH when measuring the severity of periodontal disease, carious lesions, various pathology, and endodontic trauma.1,3

Cone-beam computed tomography

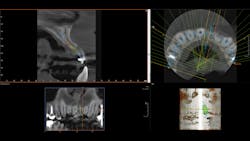

CBCTs have been used to help diagnose and treat patients within the last 20 years, and as such are considered a newer technology. A CBCT is similar to a medical computer tomography (CT) scan, but with a lower level of radiation and specifically adapted for oral health care.1,4 A CBCT is a unique digital image that uses computer software to help combine about 600 images into one giant voxel—voxel is a pixel in a 3D view—resulting in a 3D image that captures both hard and soft tissues.5

There are no current guidelines on how often a CBCT should be exposed on patients; professionals should exercise good judgment on deciding whether their patients’ needs warrant it. A CBCT can’t be exposed without specialized equipment: a CBCT imaging machine, computer, and CBCT computer software program.1 Exposing a CBCT on a patient takes about one minute.1,3,6

Specialists and CBCTs

CBCTs are very useful among certain dental specialists.1 (Currently, none of these specialists are RDHs.) Due to CBCTs’ defined ability to image bone shapes and contours of edentulous ridges in 3D, many oral surgeons turn to them to help with more accurate placement of a dental implant.1

Certain anatomy is difficult to view on a 2D radiograph, such as the maxillary sinus and inferior alveolar nerve. These structures can be seen in vivid detail on a CBCT, so many oral surgeons find them more reliable for their patient treatment plans.1 CBCTs are also not recommended for evaluating the location of third molars, except when extractions are needed, as panoramic radiographs adequately provide that information.1

In addition to oral surgeons, orthodontists and endodontists are starting to refer to CBCTs more frequently when providing care.1 Many orthodontists feel that CBCTs will replace all 2D radiographs for orthodontist cases.1 Previously, orthodontists needed multiple 2D radiographs, such as panoramic and cephalometric images, to diagnose impacted and unerupted permanent dentition and to recognize any supernumerary dentition. Research has shown that one CBCT can determine developmental anomalies and growth, with less overall radiation exposure than with a combination of panoramic and cephalometric radiographs.1

Endodontists are also using CBCTs more to help with treatment. CBCTs have been found to show pathological lesions, extra root canals, and difficult tooth root morphology in more detail than a 2D radiograph.1

General dentists are also adding CBCT imaging in their offices; when they decide to upgrade their panoramic machine, many invest in a CBCT machine due to their ability to generate a panoramic radiograph simultaneously with a 3D scan.3-5 Some dentists who place implants may feel that their practice and patients will benefit from a CBCT.1As a result, an RDH in a general dentist’s office could be asked to expose their patients to a CBCT.

But all dental professionals should remember that CBCTs, while very detailed, may miss diagnosing dental caries and providing a proper periodontal evaluation. In these cases, CBCTs are not recommended.1 In 2017, the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) met to decide if the CBCT was the next gold standard of digital dental radiography.7After a review of the benefits of both the FMS and CBCT, it was decided that a CBCT was beneficial for both implant placement and periodontal and orthodontic needs but that the FMS alongside dental probing was the best option for diagnosing bone loss.7The AAP plans to hold a meeting at the end of 2023 and will perhaps revisit their recommendations about a CBCT and diagnosing periodontal disease.7

Radiation exposure

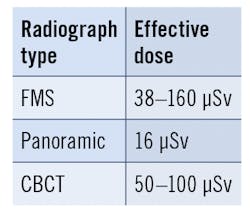

When comparing the radiation exposure of different dental radiographs, the effective dose is used for measuring radiation across different tissue types. The effective dose is measured in microsieverts (μSv) and is determined by the equivalent doses to all organs and adjusted based on sensitivity of organs.1,3 The table below shows the typical effective doses for each type of radiograph. Although CBCTs have less radiation than a medical CT scan, they still release significantly more radiation than 2D radiographic images.1 Each dental radiograph is recommended based on a patient’s needs, dental history, and chief complaint.

ALARA vs. ALADA

With dentistry shifting more with the digital age, the concepts and practices of radiology that were once taught to RDHs have evolved. Experienced RDHs learned about the principle of ALARA: as low as reasonably achievable.1,8

When RDHs remember to use the ALARA principle, they’re trying to avoid exposure that does not have a direct benefit to the patient. In doing so, the RDH must consider several factors such as the area of interest, the best radiograph to diagnose the patient’s chief complaint, and the patient’s medical and dental history. They should attempt to position the digital sensor so the radiograph they get is one of diagnostic quality with little cone cut or overlap.1

However, with CBCTs becoming more prevalent, dental professionals are asked to instead remember ALADA—as low as digitally achievable.8 This concept is in place for dental professionals to recognize several underlying principles before recommending and exposing their patient to a CBCT since a CBCT has more radiation than a 2D radiograph.8 The concern is that some dental professionals may recommend a CBCT to patients who don’t truly need one simply because the technology is newer, and the professional may not understand all the 3D radiograph’s limitations.8

Dental hygienists should recognize and understand which radiograph is best at identifying a patient’s needs. By exercising the best judgment, a dental professional would discern that in some cases a 2D radiograph may be more beneficial with less exposure than a 3D image. In addition, a hygienist could ask a patient if they have had a CBCT recently at another dental practice, and perhaps the CBCT could be shared among providers, preventing additional radiation exposure.

Continuing education

An RDH graduating from an accredited dental hygiene program is trained to be efficient in all types of extraoral and intraoral digital dental radiography1; they spend an entire semester being trained to be proficient in recognizing a patient’s need for radiographs and what type of radiograph would be best.1

Since digital radiography and CBCTs are becoming increasingly popular, more dental schools are adopting equipment to train, teach, and prepare their graduates to use during their careers.1,5,9

If an RDH has already graduated and wants to become more familiar with digital dental radiography, including exposing a patient to a digital FMS or CBCT, there are several different types of continuing education courses available.5

Conclusion

There has been an increase in the number of dental practices moving toward digital dentistry, and RDHs now have more options as to which radiographs are appropriate based on their patients’ current needs. An RDH needs to stay up to date with these ever-evolving options so they can help educate their patients on why a certain type of radiograph is warranted for their concerns.

The goal is always to adopt ALADA principles while treating patients. Many continuing education courses are offered to help hygienists become more proficient with newer digital dentistry technology, and we recommend all licensed dental professionals take specific continuing education courses and certifications on CBCT and other new digital technologies that may be available. We also hope that all dental and dental hygiene schools will tailor their radiology courses to adapt their current curriculum to include CBCT education and training and ALADA principles.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the August 2023 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Thomson EM, Johnson ON. Essentials of Dental Radiography for Dental Assistants and Hygienists. 10th ed. Pearson; 2018.

- Farman AG. Digital radiography in dental practice. Inside Dentistry. 2016;12(11). Accessed April 5th, 2023. https://www.aegisdentalnetwork.com/id/2016/11/digital-radiography-in-dental-practice

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Dental radiographic examinations: recommendations for patient selection and limiting radiation exposure [Internet]. Chicago: American Dental Association; revised 2012 [cited 2023 April 19]. https:// www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/ Dental_Radiographic_Examinations_2012.pdf

- Computed Tomography. National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/computed-tomography-ct

- Ramsey T. Which CBCT is right for your practice? January 24, 2023. https://hayeshandpiece.com/which-cbct-is-right-for-your-practice/

- CBCT Education Institute. Updated 2023. Accessed April 4th, 2023. https://cbct-education-institute.teachable.com/courses

- American Academy of Periodontology. American Academy of Periodontology publishes proceedings from best evidence consensus meeting on cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). September 28, 2017. Accessed April 2023. https://www.perio.org/press-release/american-academy-of-periodontology-publishes-proceedings-from-best-evidence-consensus-meeting-on-cone-beam-computed-tomography-cbct/

- Jaju PP, Jaju SP. Cone-beam computed tomography: Time to move from ALARA to ALADA. Imaging Sci Dent. 2015;45(4):263-265. doi:10.5624/isd.2015.45.4.263

- Beals DW, Parashar V, Francis JR, Agostini GM, Gill A. CBCT in advanced dental education: A survey of U.S. postdoctoral periodontics programs. J Dent Educ. 2020;84(3):301-307. doi:10.21815/JDE.019.179

About the Author

Tracee S. Dahm, MS, RDH

Tracee S. Dahm, MS, BSDH, is an adjunct clinical instructor for the North Idaho College School of Dental Hygiene. She also works in private practice. Dahm has been published in dental journals, magazines, webinars, and textbooks, and featured on dental podcasts. She is a key opinion leader on cutting-edge innovations in the hygiene field. Her research interests include trends in dental hygiene, improving access to dental care for the underserved, and mental health. She can be reached at [email protected].